FICTION | POETRY | NONFICTION | ART | REVIEWS

Charlotte, North Carolina:

Main Street Rag Publishing Company, 2011

Paperback, $9.95

Reviewed by William Boyle

Full disclosure: I know John Hodges. We're friends. I think he's a goddamn genius. I started in the Ole Miss MFA program the year after him. My first semester, we were in Barry Hannah's workshop together. I was floored by his stuff from the start. Barry was hard on him that semester, but it was because he knew he was working on another level, I think. I was just a fan. I read his stories and wanted more. He was prolific. He always seemed to be working on a few stories and novels at the same time. I marveled at his work ethic, the way he closed himself off, the way he got things done at an incredible clip and how the quality never seemed to lack.

Maybe none of this is important. Maybe it's in bad taste to start a review by letting the reader in on the fact that you know the writer. Maybe it gives off the feeling that, no matter what, I wouldn't write a bad review of Hodges's book. I can't say. If I didn't like Hodges's War of the Crazies, I'm not sure I'd be upfront about it. I'd probably find a way to dance around, find things to like, find nice things to say.

But I don't have to lie here. War of the Crazies is bat-shit insane. It's beautiful. It's tight. Did I say it's fucking bat-shit insane? Every sentence is a joy. In his blurb for the book, Jack Pendarvis writes: “Without imitating or bowing to anyone, [Hodges] is a real spiritual heir to his great mentor Barry Hannah.” True. Hodges is never derivative of Hannah, but the same kind of energy lights up his prose. I'd say Hodges is also the real spiritual heir to Harry Crews. My experience reading War of the Crazies was close to my experience reading Crews's The Gypsy's Curse, one of the most balls-out, wild books you're likely to find. War of the Crazies is the same kind of wonderful: strange and heartfelt, with prose to knock you on your ass.

The story takes place on some sort of hippie farm where bossman Noyo brings newcomers on board to do “slow motion research.” We meet Ruth and Silva and Skorpis and Mike, crazy one and all. Ruth is the character we're closest to, the one we feel the most for, and we experience things with her. She's young, her boyfriend has recently died, and she is fairly new to the place. The opening scene places us at a town hall meeting where upright citizens are angry at Noyo and his band of dirty hippies for raiding the dump and claiming thrown-away things. Dick Ryder, a minor character we encounter on several different occasions, stands up and says: “There's a reason that people throw away what they throw away.” Finally, the ordinance gets passed: “[No] junk shall be removed from the landfill without the written approval of the party who did the initial throwing away of whatever items that might be drawn into question.” Disaster!

This scene sets us up for a wild examination of life on the farm. People do their slow motion research, carrying things from one place to another, slowly, for no reason. Noyo fries milkweed in Dumpster grease. Mike works on a zombie novel. Silva, who has “pinched-up bubblegummy eyeballs and is missing a pinky finger,” tells Ruth about her abuse at the hands of a man named Larry Lump. He was the one who cut off her finger, telling her it would be her clitoris next. Silva tells Ruth: “[My] equilibrium has been all screwed up ever since I lost my finger. I've had these dreams about my clitoris, clitoris dreams. When Larry cuts it off, it sprouts wings. He throws it out the window, but it doesn't land on the concrete like my pinky did. Instead it takes flight. It perches on the edge of a tall building like a gargoyle, and waits for me to escape so that it can fly down and attach itself back to me.”

Hodges is obsessed with wings. When Ruth stumbles into a room with golden hay spread out on the floor, she thinks that “it looked like a nest for an angel, or maybe a large clitoris with wings, or a dead boyfriend who tumbled in at night then left in the mornings, folding his wings close to his body to fit through the window without a snag.” There is also a heart with wings painted on the wall of Silva's room, and Ruth imagines it “enfolding her, smoothing over her breasts and holding them in the warm bath of air.”

Things really get moving when Silva and Ruth hook up (Silva bites down hard on Ruth's clitoris), and Silva—clearly a psychopath of a whole different sort—becomes obsessed with Ruth. When Ruth, drunk, blows a mealy-mouthed redneck neighbor named Larry Faircloth in his truck outside a bar called Kills the Weeper, things go quickly off the rails. Soon after, Larry brings Ruth a bucket of fresh milk as a gesture of courtship, and Silva sets out on a violet rampage. All the while, Mike is working on his zombie novel, and Noyo is seeking counsel from birds.

Hodges is a master of making things new. Nothing is boring or regular on a sentence-to-sentence level. The book rambles on at an amazing pace. It's billed as a novella, but it feels much fuller than that. It's got the rhythm and pacing of a great crime novel, but it's more of a character-driven trek through a place where insane people live together in small things. “Character-driven” can be a bad label to assign to something, but I use it in the most positive way possible: there's real tension here, derived from the way characters interact, the way they talk and fight and fuck and work and go crazy. There are some genuinely frightening moments too, moments that reflect the setting in an eerie and wonderful way.

Like The Gypsy's Curse, Hodges's book is shot through with a far-out humor. It's slapstickish and surreal at points—part David Lynch, part Harmony Korine—but the characters never become one-dimensional servants to the weirdly dark and funny tone. Hodges loves to play with voices, sometimes uncomfortably so. Noyo is the character here who bears the brunt of Hodges's experiments with accent, speaking in broken English punctuated with “eh,” and Larry Faircloth and his brothers, who speak in some kind of slurry backwoods language all their own, also provide an outlet for Hodges's puckish approach to dialogue. Humor and language are at the center of the book's success: You're not going to find many writers who can balance weirdness and pure talent in such an assured way.

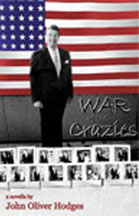

This girl I know, a reformed hippie with several star tattoos on her hands and hipbones, recently texted me to ask if I had any recommendations for summer beach reads. I hate summer, and I hate beaches. She knew I wasn't going to give her the typical bullshit, I guess. I responded: “How do you feel about flying clits?” She didn't write back. But I would've told her to read War of the Crazies. Reading it on the beach in the summer, with its scary Ronald Reagan cover (and the haunting picture of Reagan over Ruth's bed as a central image) and its words like broken glass under your toes, will keep suntanned zombies and other awful sorts far away from you. You're also likely to piss yourself, or maybe you'll start bleeding in weird places, or maybe you'll feel like some part of you will sprout wings and fly to the top of the tallest nearby building. Either way, friend, this book will fuck up your shit beautifully.

William Boyle is from Brooklyn, NY, and currently lives in Oxford, MS. He has published work in The Chiron Review, North Dakota Quarterly, Out of the Gutter, and other magazines and journals.

ISSUE:

S U M M E R

2011

MINI MAYHEM:

TALES TOLD BY

TOY SOLDIERS

By accessing this site, you accept these Terms and Conditions.

Copyright © 2010-2012 TheWritingDisorder.com ™ — All rights reserved