FICTION | POETRY | NONFICTION | ART | REVIEWS

Reviewed by Amanda Field

In reviewing An Old Junker, Howard Junker’s recent collection of blog posts, it’s hard not to also bear in mind the seven years Howard and I worked together in a small basement office that served as headquarters for the West Coast litmag, ZYZZYVA.

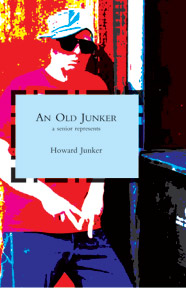

Howard is a funny man. One need not look further than the cover of An Old Junker for a portrait of the artist, a white man pushing 70 yet flashing gang fingers, his dark sunglasses mad street yet also shielding his aging retinas from sun overexposure, and the subtitle “A Senior Represents,” to appreciate Howard’s politically incorrect sense of humor.

Like any rap artist worth his tats, Howard makes no bones about calling out other literary kingpins. Dave Eggers has “fey antics”; Adam Gopnik is “more intellectual than thou”; Michael Pollan is a “demon of gluttony”; Stephen Elliott has “no literary merit.” He takes down David Remnick for publishing himself so often in The New Yorker instead of nurturing other writers; Jorie Graham for choosing her fiancé for a book prize that other applicants paid good money to enter; Dana Gioia, the “NEA czar,” for patronizing populism; Malcolm Margolin of Heyday Books for general skullduggery. The list goes on.

Howard relishes the obscure discovery, champions the forgotten masterpiece. Like some kind of library stack spelunker, he was the first to check out George Moore’s three-volume Hail and Farewell from his local university library in 51 years. At the turn of the 21st century, as the new de Young (Herzog & de Meuron) and California Academy of Sciences (Renzo Piano) buildings were phoenixing in Golden Gate Park, Howard wrote a letter to his city supervisor complaining that the Park’s turn-of-the-last—century bronze sculptures—President McKinley; Junipero Serra; Francis Scott Key—were not being adequately shielded from the meleé of cranes and cement mixers. As editor of ZYZYZVA, he personally waded through the slush pile and read—or, at least, started to read—every one of the 400 or so manuscripts that arrived over the transom each month rather than fobbing off this overwhelming task to interns as most other editors do. Looking for a needle in the haystack, finding fresh or overlooked talent, not just promoting the “Usual Suspects” as he called them, was his cause. He gave F.X. Toole his first time in print at the tender age of 69. A New York agent took note, and, long story short, Toole’s book of short stories, Rope Burns, became the basis for the Oscar-winning Eastwood film, Million Dollar Baby. Toole had been submitting his fiction to various magazines for years, but Howard could see what no one else saw because he was really looking.

At the same time, Howard has an avid preoccupation with the social elite—their club affiliations, their prep school pedigrees, their art collections—and sometimes An Old Junker reads like The Social Register. But, reprimanded by the headmaster of his prep school, where he was sent on scholarship, for wearing a flashy, second-hand jacket, he is conscious of himself as an outsider, an upstart. Howard’s many literati anecdotes could serve as the basis for a parlor game: What was Edmund Wilson’s favorite restaurant? Lewis Lapham was the grandson of a mayor of which American city? How many Stegner Fellows does it take to win a Pulitzer? He details his own faint genealogical connections to the fabulous, for example, we learn that Howard’s great-uncle Arthur had been Milton Glaser’s (the graphic designer who came up with the I heart NY logo) assistant’s grandfather’s valet. As a Newsweek arts writer in the '60s, he rubbed elbows with Andy Warhol and George Plimpton. As editor of ZYZZYVA, he sought out and published most of the notable West Coast writers and artists alive in the last quarter century. At the same time, as champion of the underdog, he helped launch into the public eye many unfamiliar writers whose names have since become nationally recognized, including Sherman Alexie, Kay Ryan, Po Bronson, among others. These discoveries are a significant part of his legacy to American letters.

As satiric as the author photo is on the back cover—Howard dressed in a pumpkin costume, swinging a softball bat—the last image of the book strikes a more somber tone: a close-up of Howard, his eyes hooded, disclosing his “unfathomable sadness and sorrow.” What are we to make of this admission, coming as it does at the end of an entertaining chronicle of a literary life? Ultimately, An Old Junker portrays a man facing his own mortality. He reports being stunned, upon beholding Vermeer’s View of Delft as a retiree, having last seen the painting as a recent college grad, that “the painting I had thought was about light is really about shade, about light being withheld, about darkness.” An editor makes his mark, often invisibly, through the exercise of his taste upon things fabricated by others. An Old Junker illuminates the resolute perspective and endurance of an iconoclast.

Amanda Field lives in Brooklyn with her family and online at amandafield.com.

ISSUE:

W I N T E R

2011-2012

ART FEATURE:

An Introduction

to Deltiology

By accessing this site, you accept these Terms and Conditions.

Copyright © 2010-2012 TheWritingDisorder.com ™ — All rights reserved