FICTION | POETRY | NONFICTION | ART | REVIEWS

Eddie LeVeque, 1987, courtesy of the author.

PART I: The Road to Keystone

Although the death of Mack Sennett on November 5, 1960 marked the end of an era, it also served as the catalyst for a renewed interest in Sennett’s films and silent comedy.

Over the next three decades, no one was more responsible for keeping alive the legacy of Mack Sennett and Keystone than Eddie LeVeque. A pallbearer at Sennett’s funeral, LeVeque kept the antics of the Keystone Kops in the public eye from 1962 until 1986, when he was forced into retirement by a broken hip at the age of ninety.

Eddie’s career in show business lasted more than seventy years, by far the longest span of any Keystone performer. By the time his diverse career came to an end, Eddie LeVeque had himself become the personification of a Keystone Kop, known to audiences as “Keystone Eddie,” the last active Keystone Kop. It was somehow fitting that Eddie was the last performing Kop; no comic ever enjoyed the role more.

Eddie LeVeque was born June 4, 1896 in Juarez, Mexico. His father, Edward LeVeque Senior, was a French businessman, gambler and money lender from New Orleans who had business ventures in both El Paso and Juarez. His mother, Carlota Carcena, came from a well-to-do family in the Mexican state of Chihuahua.

Eddie’s earliest days were spent among family in Texas and in Mexico. Eddie became especially close to his maternal grand uncle, Rito Armendariz, who had chosen a career in show business over the priesthood. Eddie recalled his uncle in a lengthy 1973 interview with Walter Wagner, published in You Must Remember This:

I’ve been in show business practically all my life. I was first influenced by my maternal grand uncle, Rito Armendariz, who became the black sheep of the family. He was supposed to become a priest. Instead, he became an impresario, a pantomime, a puppeteer who made his own marionettes, an actor, clown, writer, and musician. He also spent a great deal of his time drinking. But the bottle didn’t seem to hurt him. He died pushing ninety.

By the time I was four years old I was acting in some of his plays. I did a few boy parts, but more often I played girls, just like in the days of Shakespearean theatre. When I was seven, my parents allowed me to go on the road with Uncle Rito and his troupe. At first my mother was against it. But my father said, ‘Well it will make a man out of him. He loves show business. Let him be what he wants to be.’ We traveled and did shows in big and little towns throughout Mexico, Texas and Arizona.*(1)

It was Uncle Rito who first introduced Eddie to the new world of motion pictures. In a 1970 article written for Hollywood Studio Magazine, Eddie remembered his first movie-viewing experiences:

About 1904 my uncle bought an Edison projector and combined live shows with movies. Since electricity was not always available in some places, he used gas light in which either was part of the formula. It gave a remarkable white light. He ran mostly French films, Pathe Freres, Gaumont, Éclair, etc. They were short films. Some of these were about French Gendarmes chasing a crook up and down hilly, narrow streets, overturning push carts, and as the chase progressed more cops and civilians joined the chase until the thief was caught. These short Gendarme chases were the forerunners of the Keystone Kops.

My uncle was a movie fan, and whenever I would go home from my run away trips, we used to go together to movie houses in El Paso where we saw nothing but American pictures. I used to love to travel and would run away from home and beat my way on freight and passenger trains. I rode the SP, the GH., the Rock Island, the Texas & Pacific, the Santa Fe and other rails without paying a cent. We used to love to watch Biograph comedies.*(2)

Eddie in Juarez, Mexico, January 1902. Courtesy of Gilbert LeVeque.

Eddie’s travels with Uncle Rito lasted for three years, ending only when his uncle died. Eddie returned to El Paso, where in 1906 his father was jumped and beaten by two assailants armed with sandbags. A successful entrepreneur and sporting man, Edward LeVeque Sr. often carried large sums of money, and was consequently at risk. The elder LeVeque suffered a fractured skull in the attack, lingering for two years before finally succumbing to his injuries.

For the next several years Eddie curbed his wanderlust and remained close to home until a chance meeting with a Pathe News cameraman at the El Paso YMCA in early 1911. Almost sixty years later, Eddie recalled the fateful meeting:

In early Spring of 1911, when I was fourteen, I met a Pathe cameraman at the El Paso YMCA. He needed someone who spoke Spanish and was willing to act as an interpreter for $7 a week. I told him that I was an orphan and for the second time I ran away from home. Pancho Villa was not even a Colonel then, he was Chief of some 200 men, among whom was an American Doctor and 18 or 20 other Americans, mostly Socialists from Los Angeles who believed that Mexican peons (farm labor) should be freed from working from sun up to sun down for 18 cents a day, and from paying the debts incurred by their fathers and grandfathers in the commissaries of the rich land and cattle owners. They belonged to the Industrial Workers of the World and were derided as the ‘I Wouldn’t Work’ or Wobblies. In those days hardly any Mexican spoke English and vice versa. Thus, I became a sort of unofficial interpreter for Pancho Villa, Jose de La Blanco and other rebel chiefs with Americans in their bands.

Lewis, the cameraman, soon learned the truth that I was a runaway kid. Nevertheless, he gave me a letter of introduction to some man with the Selig Film Company in Chicago, and in June 1913 I hopped a freight out of El Paso and some three weeks later landed in Chicago. At Selig I was told that things were quiet, but to try the Essanay Studios or the American Film Company. The American Film needed a helper in the lab, soon I was playing messenger or office or delivery boy. Jack Warren Kerrigan and Vivian Lester were the stars and Richardson the Heavy. The company opened a Studio in California to make Westerns, but I returned home. Villa was now a Generalissimo of the Northern Division. I often rode in his auto with the Chauffer, a redheaded boy of 15-years old and old school friend. As Villa sat with other officers in the back, he used to point to me as his blond son [El Guerito] and to the chauffeur as his redheaded son.*(3)

In 1973, Eddie spoke to Walter Wagner about Villa in great detail:

He was a short man with wide gaps in his teeth who wore a long mustache. A friend of mine was Villa’s chauffeur. He introduced me to Villa, who promptly made me his interpreter. It was exciting for a while but, after a short time I got bored. And it began to dawn on me that I was working for a man who took pleasure in robbing, terror and rape. He was exploiting the same peons he was supposed to be helping, though I never saw any of that personally. All we’d do was visit one city after another in his big seven-seat open black touring car. The only break in the routine with Villa was when news photographers from the United States turned up. Villa loved to pose for them, and they were fascinated by his colorful reputation. Villa was the biggest publicity hound I ever saw, worse than any movie star. He’d let them shoot pictures of him as long as they liked. I was frequently in the snapshots. Once I borrowed a gun from a member of his gang and posed alone with Villa. Traveling with Villa was really monotonous, so one night I slipped out of his camp and walked sixty miles to El Paso. I’d decided by now that I was going to Hollywood.*(4)

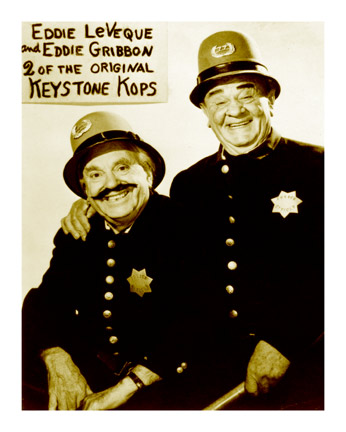

Eddie with lifelong pal and fellow Keystone Kop, Eddie Gribbon.

Courtesy of Gilbert LeVeque.

In 1970, Eddie described his journey from El Paso to Keystone:

I wanted to travel in comfort, so I became a news butch (news agent) in passenger trains selling postcards, magazines, souvenirs, etc. In June 1915 I went to work as a prop boy, bit actor and Keystone Kop. In those days everybody played Keystone Kop at one time or another, even the big star comics such as Fatty Arbuckle, Ford Sterling, who usually played the Chief, Harry McCoy, Bobby Dunn, and others. It was just as hard to get into pictures then, as it was later. I had three or four 8 X 10 stills of myself in some of the American Film Co. pictures which, by the way, consisted of brief stories of about a half reel, the other half reel usually was about how sardines were canned, or bottles made, etc. I approached Harry Atkinson at the casting window, and showed him my stills. He was not impressed. It was about 8 A.M. and there must have been about 20 people, including children, standing on the sidewalk hoping for a call. Along with my stills, I had some postcards of the Mexican Revolution with me standing along side Pancho Villa and men of his band. That caught Harry Atkinson’s eye and interest. Charlie Avery, actor and director, was just going out on location. Charlie needed an extra prop boy to assist the cameraman, and whatever else might turn up. Harry told Charlie that I was not only an actor but had been assistant cameraman to a Pathe newsman taking pictures of the Mexican Revolution. Although World War One was several months old, the Mexican Revolution and Pancho Villa had caught the imagination of the American people. Eddie Gribbon took me under his wing and helped correct my English and we became intimate pals until he died in 1965. Jack Dillon, Eddie Cline, Charlie Avery, Harry Atkinson and others took a liking to me, since I used to show them the best places to eat good Mexican or Spanish food, as well as helping them meet handsome Mexican Senoritas of the upper class, refugees from the revolution.

The fellows at Keystone used to kid my English, and the more they kidded me the more mistakes I purposely made. It had been the same at the American Film Company. But I had learned that by pretending I made glaring speech mistakes, besides being overly polite, was a humorous attraction to older fellows who would take me places just to show me to their girls. Some of these fellows were directorsand big actors, and it was the same at Keystone.

I first ran into Fatty Arbuckle about 1909 or 1910, he was doing a vaudeville act at the Happy Hour Theater in El Paso, a high class vaudeville theatre and movie house. It was late afternoon and he was standing in front of the theater talking to the owner. I asked for a job as a projection assistant, and Fatty said that I could have the job if I went to the Unique Theater and borrowed their left hand key to raise the curtain. The manager at Unique told me to try the Wigwam theater, but the owner, Mr. Lynch, who had been my father’s friend, told me that they were fooling me. I pointed to Fatty as the one who sent me on the errand. Mr. Lynch told me to tell that fat guy that he was a bum and to run. Returning, I called Fatty that and I ran, he pretended to chase me. When I looked back, be was laughing his head off. At Keystone, Fatty didn’t recognize me, and he used to hand me a dollar bill with instructions to get a whale sandwich or elephant sandwich, or some other crazy thing. One time he gave me five dollars, told me to keep the change, and to go from store to store downtown to buy some ridiculous merchandise that didn’t exist. I did go downtown to the Pantages instead. Later I told him that I went from store to store and the lady clerks had been shocked. He, Slim Summerville and others got a big kick out of my story.

Fatty told me to keep the five bucks, which I knew he would. A couple of days later I asked him if he wanted me to go on another errand. He looked at me with a quizzing eye and said, ‘Who has been kidding who? Have I been the sucker all the time?’ Then I reminded him of our first encounter in El Paso. He laughed and shook his head. He was a great and generous sport. We used to work for $3 a day, and $5 if you furnished your own tuxedo. But room and board with breakfast and dinner and lunch and your clothes washed was only $5 a week. For amusement, there was Solomon’s Penny Dance on Grand Avenue. Car fare was only five cents and ice cream sodas were a nickel. Excellent Italian or French restaurants served meals for 25 cents, you could have a glorious Sunday till late with a girl friend for $1.50.*(5)

Buster Keaton on stage with Eddie and the Keystone Kops at the Movieland Wax Museum, May 3, 1964.

In a 1967 interview with Bill Erwin, written for the El Paso Times, LeVeque reminisced about his early days at Keystone:

I was actually more than a property man, because back in 1915 we all did everything. If an actor was suddenly needed, we dropped our props or our hammers or whatever and got in front of the camera. We assisted the director, doubled for the women, adjusted the reflectors, played bits and made ourselves useful wherever we were needed. Our pay was $3 a day.*(6)

Six years later, Eddie elaborated on the same subject with Walter Wagner:

From prop boy I graduated into doubling for girls. When one of the female stars on the lot couldn’t do a stunt or a fall, I’d put on a dress and do it for her, things like jumping from a speeding automobile or trolley car. I’d take the pratfall. I was agile and it came easy for me.*(7)

It was around this time that Eddie first got the chance to play a Keystone Kop, the role of a lifetime, as it turned out. Looking back upon his days as a Kop, Eddie recalled:

When we started shooting a Kops picture, we never had much of a script, just a story line that more or less gave us the beginning, the middle and the end of what the picture was supposed to be about. Before a Kops sequence, the director would say, ‘All right, boys, do what you want, do what’s funny, only don’t hurt yourselves.’ That was the only ‘direction’ we received.

But it was strange, once we were in the car and the chase began, there was an exhilaration that came over you. You forgot yourself, and you just took chances. I took many a fall that was unnecessary, but everyone was trying to outdo everyone else. There was always that spirit of good-natured competition. The only thing that mattered was to make it funny. On the screen it looked like we were traveling zooosh, one hundred miles an hour. Actually we were going about forty, which was still dangerous when you leaped from a moving car. The fast chases were trick photography. The film would be speeded up mechanically. For the collisions we used what was called a moving panorama. It was a painting with trees and telephone poles and city buildings and trolley cars. A couple of carpenters or propmen would turn it, and the panorama moved, giving the impression that when our cars just bumped into each other lightly, actually we were in a head-on crash. Then, of course, we’d fall out of the cars and do flops, and it all looked real on the screen.

The pictures gradually became more sophisticated when we started using stories where the plots were laid in the city. But in the first ones everything was rural, countrified. There was the farmer, his daughter, the stupid boy who wanted to marry the farmer’s daughter, the tramp in the haystack and the villain with the high hat and long coat who held the mortgage and had an eye on the girl. He was always promising to take her to New York. When she resisted his advances, the trouble started, and the father called the Kops.

The chase was the heart and soul of all the Kops’ pictures. But there were sight gags interspersed with the chases. And close calls. Once they put me in a small shack, and two piano movers left a piano in front of the door. Then the shack was set on fire. The gag was supposed to be my trying to get out. But I couldn’t get out. I really couldn’t get out. The other Kops started throwing water on the shack. The piano was a breakaway, but for some reason it didn’t break. When the other Kops realized my screams for help were for real, they rescued me by smashing the piano with axes. None of this, of course, was in the script. But the camera kept on cranking. It turned out to be one of the funniest parts of the picture.*(8)

Like so many other bit players, LeVeque occasionally found work off the Keystone lot. While moonlighting, Eddie was hired as an extra by D.W. Griffith for his 1916 epic, Intolerance. Eddie performed numerous roles in the film. Killed off in one scene, he would reappear moments later as another character.

Though he was at Keystone for almost two years, it is almost impossible to pinpoint which films Eddie worked in while there. Because LeVeque was not a major performer, he was not listed in cast credits and film production scripts. Studio payroll ledgers also fail to mention him. Bit players were listed only as “extra,” and their names were seldom noted in the records.

The scant amount of factual information available about Eddie’s days at Keystone was frustrating not only to the author, but to Eddie as well.

In 1971, Eddie sought out the few surviving old timers he had known at Keystone and asked for their help in recalling the films he had worked in. (At one point, Eddie was collaborating with a writer named Jory Sherman to do a book on his life story. The memories shared by his old Keystone mates may have been intended for use in Sherman’s book —which was never published—or may have been needed by Eddie to help fend off legal challenges regarding his ownership rights of the Keystone Kops name.)

Minta Durfee Arbuckle recalled:

In going over my scrap books, I ran into some publicity about the Keystone Kops and you were mentioned. Also, another ‘bit’ of publicity that you were called ‘Chile’, ‘Mex’ and eventually Eddie LeVeque.

You had a hard time with English but you have done well in learning our English. Being young at the time you [sic] worked at Keystone it was easier for you to learn. Just wondered if you remember those days. They were great days and a wonderful place to work. Nice to know we made the world laugh. Not many laughs any more.*(9)

Erle C. Kenton remembered that, “In 1916, when I was Bob Kerr’s co-director at the Keystone-Mac Sennett lot in Edendale, Eddie LeVeque played a waiter in one of our comedies.”*(10) (Editor’s note: The film described by Kenton may have been Black Eyes and Blue but I have not yet been able to substantiate this.)

Chester Conklin stated that, “before World War One, when I was at the old Keystone-Mack Sennett lot, Eddie LeVeque played a ‘jailbird’ in one of my comedies, titled: Dodging His Doom (1917). Like most everyone of us, sometimes he played a Keystone Kop.”*(11) (Editor’s note: A partial print of Dodging His Doom, considered lost for many years, was discovered in the Library of Congress film collection, under the title Without Hope, by Brent Walker in the summer of 2003.)

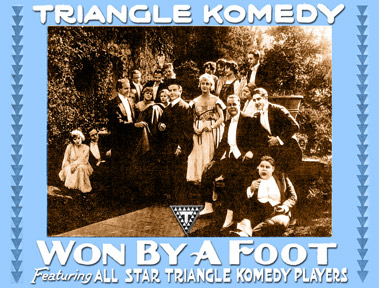

Eddie Sutherland, who went on to a long career as a top-notch comedy director after leaving Keystone, was a lifelong friend of LeVeque’s. Sutherland remembered making a movie at Keystone which featured a college football game. (Editor’s note: Won By A Foot (1917).) As he crossed the goal line and scored the winning touchdown, Sutherland was tackled and buried beneath a pile of football players, squashing him. He heard the director yell “cut,” but yet someone continued jumping up and down on the human pile-up, leaving him stuck underneath. Glancing up through the heap of actors laying on top of him, Sutherland was able to spot who the acrobatic wise-guy on top was — his buddy, Eddie LeVeque!*(12)

Less than two months after Won By A Foot was finished, on April 6, 1917, the United States declared war on Germany. While on vacation in San Francisco in early May of 1917, Eddie enlisted in the U.S. Army, and joined the Army Air Service Corps. Eventually he was transferred to Texas, where he spent most of the conflict at Kelly Field.

When the war ended, Eddie returned to Hollywood, but his days working for Mack Sennett and Keystone were over.

I never went back to Keystone, not even for a visit. My apprentice days were over.*(13)

Lobby card from Won By A Foot. Original is in the collection of Mike Hawks.

END OF PART ONE

Next Issue: Part II – The Return of the Keystone Kops

Acknowledgments:

I would like to thank the following people for their invaluable help in piecing together the life and career of Eddie LeVeque: Faye Thompson at the Margaret Herrick Library for her support and assistance in guiding me through the massive Mack Sennett collection; film historians Sam Gill and Brent Walker for sharing their considerable knowledge of silent comedy; and most of all I wish to acknowledge and thank Gilbert LeVeque. Gilbert spent many hours helping me gain insight into his father’s career. It is through his generosity and kind permission that many photos from Eddie LeVeque’s personal scrapbook have been brought to light and published with my article.

The Writing Disorder would like to thank Steve Rydzewksi and his publication SLAPSTICK!,

where this article originally appeared.

Top photo: The author (right) with Eddie's son Gilbert LeVeque at Griffith Park during a recent visit to Los Angeles.

Michael Campino is a freelance writer and historian whose writings have frequently appeared in Slapstick! magazine. He has also contributed to and assisted in the production of numerous books and articles. A native of New York, Michael resides in the San Francisco Bay Area with his wife Deirdre, two daughters, and the family cat. He is currently doing research on the Mack Sennett Bathing Beauties for a projected series of articles.

ISSUE:

S P R I N G

2011

THE NEW

RULES OF

W R I T I N G

By accessing this site, you accept these Terms and Conditions.

Copyright © 2010-2011 TheWritingDisorder.com ™ — All rights reserved