Illustrations by Claudia Kilgore

I want to make one thing clear from the beginning. You read this at your peril. The only reason I am putting it all down on paper is in the hope that doing so will expunge it from my mind. My ability to destroy this recounting, once finished however, is not possible. Ripping it asunder, or burning it, would only multiply its evil. However, it is my fervent desire that this manuscript never be found. That is why I plan to bury it. I shall entomb it with the rest of the dead and rotting detritus of the world. If you come upon it, which apparently you have, proceeding beyond this paragraph would be a grave error. Best to return it immediately to where you found it. Should you continue, you are likely to find yourself in the same wretched state in which I reside. But more importantly, the responsibility for dealing with this all consuming malignancy will become yours alone.

You have been warned.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Mine was a life of no particular distinction. I was one of countless bureaucrats laboring unseen in the bowels of government house. My title was file clerk. I was by no means the only one. In my department alone there were four of us. We were responsible for separating, cataloguing, and filing a seemingly endless number of documents, reports, forms, letters and memoranda that members of parliament initiated, responded to, or simply wished to have available in the future. The state, in its infinite wisdom, felt that maintaining mountainous volumes of correspondence was absolutely essential to both the preservation of history and the orderly operation of political authority. I saw no reason to disagree as this afforded me a stable income.

Looking back, I long for the mindless monotony it once provided. The comfort of routine that is so foreign to me now. We humans seem incapable of truly appreciating peace and complacency, until they are replaced by havoc and anxiety. If only I had not volunteered. If only I had been content to maintain my status as an unseen cog in the wheel of bureaucracy. But no, I leapt at the chance for something new, something different.

Be mindful of what you wish for. But you won’t listen. If so, you would not have come this far.

“I know this is highly irregular,” he began, as my colleagues and I stood in front of his desk, our hands pressed stiffly to the sides of our trousers. He didn’t like irregularities. They interrupted his illusion of control. “But apparently our section is being queried as to whether any of our file clerks would voluntarily accept temporary assignment to F branch. Pish-posh, if you ask me.”

“I would, sir.” I can still hear myself say. Three words I shall regret for eternity.

“Oh you would, would you? Our corner of the world not good enough for you, is that it? Anyone else? I didn’t think so. Right, then. See Featherstonehaugh, Foreign Branch, level two. I still say pish-posh.”

Featherstonehaugh was as supercilious as his name. He wore his disdain for those beneath him like a horse wears a bit, with undisguised annoyance.

“You’re the volunteer, are you? Best Records Branch could do?”

“I’m sure I can’t say, sir. But I did volunteer. So here I am.”

“How enlightening. Do you have your curriculum vitae?”

I handed it to him.

“Less than impressive, I must say,” he said, before he could possibly have read it. “But no matter. It’s a thankless task in a fetid backwater. Should be perfect for you. Please listen and don’t interrupt until I’ve explained the assignment in detail. Then ask questions, if you must. Are you with me so far?”

“I am, sir.”

Upon that note, Featherstonehaugh proceeded to outline the task for which I had, without reserve, volunteered. It consisted of a journey to the far side of the world. As he droned on, he attempted to make it sound as distasteful as humanly possible. But his condescension was all for naught. For one as inexperienced as I, it sounded like a gift from heaven. An excursion across seas and continents. An assignment not beyond my competence. A specified amount of time to accomplish what I was being sent to do. A return trip home. All at the expense of his majesty’s coffers. I was so enthralled I failed to realize he had stopped talking seconds earlier.

“I say, have you been struck mute?”

“No, sir. Sorry. I am not mute, sir.”

Handing me the detailed itinerary he had read verbatim, he asked, “What questions do you have?”

“No questions, sir.”

“No? How sporting. Dismissed,” he said offhandedly, having already turned to the more important matter of smoothing his moustache.

One week later, at Royal Albert Dock, I boarded the good ship, South Wind. I refer to it as a good ship now simply because that seems to be how steamers are referred to these days. I had no way of knowing whether it was a good ship or not, never having been on a ship in my life. But it seemed a good ship, immense with multiple decks and a smokestack that belched black soot into the gray sky. Like most of the passengers, I had chosen to stay topside for the embarkation, even though there was no compelling reason to do so. There was no one on the dock to which I would wave farewell. My adult existence to this point had been as solitary as it had been unremarkable. No wife. No sweetheart. Acquaintances, but few friends. Certainly none of sufficient fondness to travel to the harbor to wish me bon voyage. What little family remained were aunts, uncles and cousins made distant more by apathy than lineage. But I stood on the deck, watched the outline of the shore grow faint and let the past slowly fade away. I was setting a course for the future, changing my life for the better. I was confident my bold initiative had set me upon a tide of good fortune. This would not be the last time I would misread the tealeaves.

As the first day of my journey lengthened into evening, we passed through the Channel, skirted the coast of France and made our way into El Mar del los Vascos,

the Basque Sea. I was content to stay on deck and watch the far shore for the many fishing villages and shipbuilding ports I had read so much about. I confess that virtually all of my knowledge of the world, at that time, had been gleaned from pages of books and frequently folded maps I often perused in the public library. Actually seeing the coastline, I felt freer than I had ever been. No longer bound by geometric intersections and dewy decimal aisles, I was skirting the coasts of foreign countries, savoring the wind and spray in my face, basking in the anticipation of potential adventure.

I stayed on deck until the sun fell below the horizon and there was nothing left to see but the wake of the ship churning through the moonless night. Then I returned to my cabin, undressed and prepared for bed. The cabin’s length was barely the length of the bed itself. It’s width perhaps twice that. No complaints, mind you. It was only by the good graces of the government and my aforementioned volunteerism that I was taking a sea voyage at all. But it did feel a bit like living in a closet, or a cocoon. No need to go on about it. I just wanted you to know I wasn’t traveling in the lap of luxury. It was a reasonable accommodation for a single individual. More appropriate for someone three inches shorter than myself, actually, but I digress.

Prior to falling asleep, I reread the itinerary and instructions Featherstonehaugh had given me. I would do so every night of my journey, rapt as I was in the excitement of it all. After Spain, Portugal, and the Straights of Gibraltar, it was the Mediterraian Sea to Alexandria. There, I would take a train to Cairo and board a smaller vessel that would cross the Red Sea to Djibouti. From there, another boat across the Arabian Sea to Bombay. By train again to Madras, boat to the Bay of Bengal, up the Adaman Sea to the Gulf of Martaban, and eventually to my final destination, Rangoon.

I was to be met by M. Henderson of the Foreign Office who would escort me to the quarters that had been arranged for me. The following day I would be taken to the offices of Doctor Leland Jonas, and my project would begin.

Featherstonehaugh had given me a dossier on Doctor Jonas. The crux of which revealed him to be a brilliant man. Highly educated not only in medicine, but also in botany and entomology. But, Featherstonehaugh had added with a snide riposte, apparently certifiably insane and hopeless at organization. Doctor Jonas had supposedly hanged himself and left his office in a state of unimaginable squalor. The local native population refused to enter the doctor’s office after his death, apparently put off by one or another of numerous superstitions relating to the region. A previous trip to his office in Rangoon by members of the foreign service had uncovered such a voluminous amount of notes, specimens, memorandums and unfinished reports, all in such a chaotic state, as to make the examination of his findings virtually impossible. It had been decided that until his work could be codified into some sort of logical orderliness, nothing of value could be achieved. Ergo the need for a file clerk.

The idea of reassembling a suicide’s disordered life was not that compelling, but the opportunity to see a part of the world I never imagined I would ever encounter was thrilling. It was necessary, however, to revisit the study of plants and bugs I had given scant attention to since leaving university. Not to mention looking into medicine, which I had virtually no knowledge of whatsoever. So I would spend part of each evening prior to sleep, reading and making notations in the three volumes I had purchased prior to embarking. They were laborious tomes, to be sure, on botany, entomology and the healing arts, but they would at least give me rudimentary information I could use in my work.

By the time we reached Alexandria I had tired of the ship. So it was not without some measure of enthusiasm that I looked forward to the train ride to Cairo. I must admit though, that I was ill prepared for the heat, and spent the majority of time with my head beside the lowered window to capture the breeze. There was little to see other than vast expanses of sand and the occasional procession of men and camels who seemed to glide effortlessly along the desert floor, more part of the land than interloper.

The boat we boarded in Cairo was infinitely smaller than the ship I have previously discussed and the passage was untroubled. So I soon found myself boarding another train from Bombay to Madras. The train station virtually teemed with humanity. I had thought the previous Egyptian crowds were large, but they paled in comparison to the sea of Hindu and Muslim skin and bones that seemed to throb as one, like some giant pulsating animal. I breathed a sigh of relief when I was finally able to take my seat. Once the wheels began to turn, I must admit I fell asleep almost immediately, fatigued by days of travel.

The boat I took down the Bay of Bengal was the smallest yet. It could not have consisted of more than ten cabins. The passengers were as irrelevant to me as my previous traveling companions had been. I was focused solely on the country where I would soon be alighting, Burma. We docked fourteen days from my initial departure. I now felt that I was on the far side of the world.

The rainy season had begun. We disembarked amid steady precipitation. I stood on the deck, beneath the shelter of the overhang, and scanned the crowd. I hoped M. Henderson would be in uniform, as I had no other means of identifying him. Luckily, I soon spotted a tall man in military attire stepping out of a waiting automobile, umbrella in hand. Pulling my hat tighter on my head, I started down the gangplank waving as I walked. I approached him and asked, “Are you M. Henderson?”

“I am. Are you the file clerk?”

“Yes.”

“This way, then.”

Once inside the motorcar we exchanged more familiar introductions. Despite his somewhat stiff demeanor, he seemed to be an affable fellow and welcomed me warmly. The streets by the harbor were narrow and pedestrian traffic was heavy in spite of the inclement weather. I was fascinated by the people. They seemed so different. A tiny race, I thought. So small. Brown and wafer thin. Many would smile and wave as we passed.

“Not used to seeing a motorcar,” Henderson explained. “Many of them have little exposure to the outside world. They’re filled with strange ideas and foolish superstitions. But some have done a first-rate job of picking up English. Like Doctor Jonas’s boy, Patu, at your house.”

“Doctor Jonas’s boy? Will I actually be staying in the doctor’s house?”

“Yes. They were his quarters.”

“Was the house…where he…”

“Oh, no. Don’t lose any sleep over that. He laced up the ghost’s necktie at his office. That’s where you’ll be working. But you won’t have to spend your nights there.”

Somehow, I was less than comforted.

The house was in a part of the city where narrow streets widened into boulevards and massive walls shielded homes and buildings behind them. Stopping at the appropriate spot, the driver exited the car, opened the gate, returned and drove us into the courtyard where Henderson bade me farewell.

“I’m afraid I have a number of things still to do. Mustn’t dally. Patu will greet you, make you comfortable and show you to the office tomorrow. It’s just a short stroll from here. If you need anything at all, ask Patu. He knows how to get in touch with me, and just about everyone else of consequence. Good luck with your… filing. Perhaps we can have dinner one evening.”

I was about to respond but the motorcar was pulling away before I had the chance. Walking to the front door, I put down my valise to grip the brass knocker when the door opened and a diminutive fellow in black pants and a white tunic opened the door, bowed, and said, “Greetings to his exalted Majesty’s most esteemed and revered File Clerk. I, Patu, welcome you.”

Never having been esteemed or revered, I was a bit lost for words, but I managed to reply, “Good day, Patu. I’m very happy to be here and I put myself in your capable hands.”

He took my bag, stepped aside and motioned me into the foyer. I stepped inside and was immediately overcome with my good fortune. The house was far grander than I had imagined. A number of rooms rimmed the circular entry. Their doors were open and I could see the gardens beyond. Lush, green ficus leaves were interwoven with bamboo and teak trees. Red, white and yellow hibiscus shimmered with color. Surely no man could be as lucky as I.

Patu made rather a show of walking me round and pointing out each room. He had obviously rehearsed it for some time and took pleasure in showing off his English as well as the house. I liked him and his rhetorical flourishes immediately, and so responded at the end of his tour by saying, “Patu, these are the grandest accommodations I have ever had. Thank you for sharing them with me.”

“Shall I bring you a gin and tonic water in the library? Doctor Jonas, may peace be upon him, always took his there.”

“That will be fine. Thank you.”

An hour later I was enjoying my second gin and tonic as I thumbed through some of the doctor’s books in his library. But I couldn’t keep my mind on them. As I sat back and gazed out into the garden where the sun was just beginning to fall beneath the horizon, it struck me that I had perhaps never been happier in my entire life than I was at that moment. Of course, I had no way of knowing, that would be the last time happiness would ever again be part of my thoughts.

On the way to the office the next day, Patu insisted on walking behind me. He would tell me at which corners to turn, but he said it was unseemly for him to walk in front or beside me. I agreed, not wishing to debate what he felt was customary. On Bigandet Street we passed St. Paul’s Catholic School for Boys and came upon a building close by built entirely of teak in the Anglo-Burmese style. Patu handed me a key and said I should go in. Down a long hallway, on my left, I would find Doctor Jonas’s office, he said.

“Aren’t you coming with me, “ I asked.

“No Burmese will enter the doctor’s office now. Enough time has not passed.”

“Time for what?”

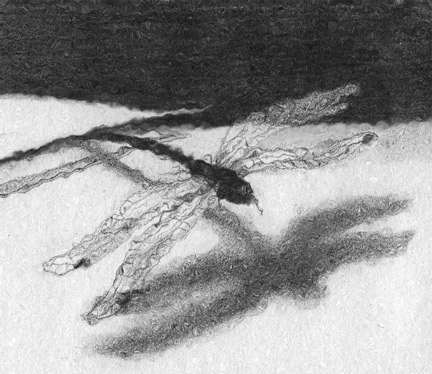

“Time for the brokenhearted dragonflies to leave. No Burmese will enter until they are gone.”

“Dragonflies with broken hearts? I’m afraid I don’t understand.”

“The English do not understand. Nor do they believe. The Burmese know better. I go back to the house.”

Must be one of the superstitions Henderson and Featherstonehaugh spoke of, I thought. So I said to Patu, “Fine. I’ll see you at the house tonight.”

Following his instructions, I walked down the hall and found a sign that read LELAND JONAS, MEDICAL DOCTOR. The door beneath it was indeed locked, so I took the key Patu had given me and used it to enter. Whereupon, I was immediately cognizant of a high-pitched sound that seemed to hang in the air like violins out of tune. The further into the office I stepped, the louder the drone became. I walked to the only window I could see, thinking a breeze might help dissipate whatever was making the sound. The window would not budge. Setting down the books I had brought with me, I put both hands and all my strength to the task. It moved not an inch and the tone continued unabated. I walked back to the door and closed it. The sound immediately stopped. How very odd, I remember thinking.

As I had been informed, the office was a catastrophe. Floors, desks, tables and chairs were strewn with papers. Equipment stood willy-nilly around the room. Microscopes and specimen plates peeked out from surfaces cluttered with debris. Vials of medicines and drugs, even syringes and surgical equipment were all about the place as if tossed by the wind. I saw another door on the far side of the office. Perhaps an examination room. Opening it, I found more of the same. Immense stacks of paper, journals, notes and pages torn from books. It was as if the doctor, like a giant Burmese python, had shed his various skins here and there and left it all to be reconstructed by anyone foolish enough to take on the task. The locals would have none of it. His superiors hadn’t wanted the job. Why, was now obvious. One must pay the piper, I said to myself.

Even though I assumed that a large part of what lay before me was simply an immense amount of refuse, I decided to make a start. I took off my jacket and draped it around the back of the desk chair. While doing so, I noticed that some of the decorative molding on the front edge of the desk had been broken off. Seeing nothing on the floor, for some unknown reason I looked up and spied a large exposed beam running the length of the room, just below the ceiling. My God, said I. He must have climbed up on the desk and used that very beam. Looking again to make sure the door was still closed, I climbed up on the desk. The distance between it and the beam seemed just enough to do the job. The molding was probably kicked loose by the involuntary spasms and twitching of his legs. Or perhaps, having stepped off the desk, he began to have a change of heart as the noose tightened, and struggled unsuccessfully to regain his footing. Suddenly my knees became rubbery, aided no doubt by an overactive imagination. I quickly came down and took a seat in the desk chair. An ever so slight wave of nausea made itself known briefly, but quickly passed.

Concentrate on the task, I told myself, not on the sordid circumstances that brought me here. So I set myself to it.

Fixing my gaze on the largest heap of paper and debris on a table in the corner of the office, I decided to begin there. I walked over and reached for a handful of documents. As I pulled them from the pile, and was about to return to the desk, my peripheral vision sensed the smallest movement from where I’d removed the papers. Imagination again? Playing tricks perhaps? I paused for a moment peering at the spot. The edge of one piece of paper did seem to rise, almost imperceptibly. Did it really move? Was it just settling, or perhaps put in motion by the tiniest breeze? But I reminded myself the window was closed and the door was shut.

The paper was still now. Probably nothing, I thought. But just to convince myself I had been mistaken, I reached over and began pulling the piece of paper out ever so gently. The moment it was detached from the other papers surrounding it, a black dot bolted furiously up the length of my arm, heading directly toward my face. I began to back peddle as quickly as I could. The dot had somehow sprouted luminescent wings and was flapping them wildly, jittering up and down in front of my eyes. It was moving so rapidly I couldn’t focus on it. I raised my hand and tried to brush it away but it was moving too erratically for me to strike. Before I knew it, the drone I had heard upon entering the office started again. Then another dot and another emerged from the heap of papers. Instantly, they had multiplied exponentially and a huge swarm of them began to hover near the ceiling as the high-pitched whine became louder and louder. Still trying to fend off the one who had raced toward me initially, I became aware of a monstrous sight. The winged insects started literally exploding in mid-air, their chests blown apart as if by tiny explosives. One by one they burst into a haze of minute green particles that hung in the air like dust mites. Yet still the largest one came directly toward my face, as if to attack. In my haste to recoil swiftly, I stumbled and fell. My head banged into the leg of the Doctor’s desk. A sharp pain knifed along the base of my skull. It made me wince and bring my free hand up to touch the offending spot. The touch reignited the pain and I grimaced, instinctively inhaling to let go a sigh. When I did, the winged apparition dived headlong inside. I could feel it bouncing from my tongue to my jaw to the roof of my mouth. I began to gag. For a moment there was stillness. I thought perhaps I had spit it out. Then the fluttering began again. I could taste its dry thinness careening behind my teeth. I tried to use my tongue to force it forward. I opened my mouth wide and reached in with my hand to grab and extract it. I felt nothing. I spat and spat again. It’s gone, I thought. I’ve gotten rid of it. Then a violent flutter arose once more. I stretched my jaws as wide as they would go and reached in with my hand to rake it out. Immediately its ferocity increased, and I realized it was plummeting down my throat. I began to gag profusely and choke simultaneously. My throat caught. My stomach turned. I coughed and tried to spit, but the saliva stuck in my throat and made me gag again on the air being sucked into my windpipe. Tears emerged from my eyes. I brought both hands to my neck, heaving and coughing and spitting at the same time. I felt unable to breathe. My heart was racing. I must stop this, I thought. I must. Against my will, against every instinct I had, I swallowed deeply. Not once, but twice. Then I lay on the floor, still and quiet. I raised my knees to my stomach, as a fetus might. It’s gone, I kept telling myself. I’ve swallowed it. I will not choke. I will not vomit. I will not die. I will simply be still. It’s over.

And soon it was. My breathing eased. My pulse slowed. I regained my composure, if not my dignity. Surely, it was only a moth I thought, nothing more. How could I have panicked so completely. Still, the thought of it, within me, made me sick to my stomach. Perspiration spotted my brow. I noticed my hands shook slightly unless I gripped the desk. What time was it? How long had I slumped there before rising to sit in the chair? How long had I been sitting? What happened to the papers I had taken from the pile? I saw them scattered about the floor. I still don’t feel well, I told myself. Fresh air. I need fresh air. I shall go outside. Go back to the house, perhaps. Rest a bit. Before returning to begin the work again. Insects, that’s all they were. Perhaps as Patu said, dragonflies. Were they that large? I could not remember. But I could still see them exploding in mid-air. Bursting apart and dissolving. And I could still feel the flutter of wings that fled down my throat.

I retraced the route I had taken that morning with Patu, my forearm resting against my stomach as I walked. I could tell I was stooped over, but it seemed too much effort to stand erect. Half way to the house, the skies opened and rain came down in sheets. I was soaked but could not force myself to quicken my step. I slogged along the streets until I reached the house.

Patu met me at the door, brought me inside and helped me out of my wet clothes. I told him I needed to rest and retired to the bedroom. Crawling into bed in the middle of the day, I planned to take a quick nap and return to the office later that afternoon. When I awoke the moon was up.

I went downstairs and called for Patu. He came and asked if I was feeling better.

“I’m not sure. How long was I asleep?”

“Two days, almost three now,” Patu replied.

“What? It can’t have been that long.”

“You were very ill. A fever, I think. Your sleep was fitful. You cried out and waved your arms at the air.”

Was it a dream, I wondered, had it happened at all? “Patu, I did go to the office, right?

Then I came home, wet from the rain?”

“That is correct. Then you fell into a fever and slept. I informed his most benevolent and militaristic M. Henderson that you were ill and would be spending some time here before returning to your work. He stated your sickness was perhaps caused by your long journey?”

“I don’t think so, Patu. Let me tell you what happened.”

As I recounted all that I remembered, Patu listened and spoke not a word. The longer I talked, the more his face grew sullen, eventually grave. He seemed to back away from me as I spoke while pulling his body into a crouch, as if trying to become even smaller than he already was. I knew something was terribly wrong.

“What’s the matter, Patu? What have I said that’s alarmed you?”

“The brokenhearted dragonflies. You saw them. And heard their mating song. Each struggles to be heard above the rest. To win the right to mate. They sing with such force, their bodies cannot contain them. They shatter, like glass. You saw them.”

“I saw something. But surely what you describe is only a myth. It can’t be true.”

“The English never believe until it is too late. Doctor Jonas finally believed. Too late.”

“What do you mean? Tell me what you know of Doctor Jonas.”

“He studied many insects and flowers, looking for ways to heal the sick. I asked him not to collect the dragonflies. But he would not listen. He too called what you have seen and heard a myth?”

“He heard them? He saw what I saw?”

“Yes. And like you, he was invaded by the queen.”

“Invaded? What do you mean, invaded?”

Patu went on. “The dragonflies are brokenhearted because they want to mate. They do not know that the queen has already mated. She shuns them and they destroy themselves. But she does not care. All she seeks is a dark, wet place to lay her eggs.”

My stomach twisted violently. I thought I was going to be sick. But I managed to say,

“Utter nonsense! What are you talking about?”

“Doctor Jonas was a good man. Once he learned what he must do, he did it.”

Both my patience and my strength were wearing thin, I shouted at him, “Stop being so damned mysterious. Tell me all of it. Now!”

“I must not.”

“You must. I insist. Go on.”

“When the dragonfly queen invades, she lays her eggs and they begin to hatch. Once born, they must have food. They take sustenance wherever they can find it. They begin to eat the body of the host.”

I immediately felt nauseas again. He couldn’t be serious, but I couldn’t stop listening.

“The organs. The muscles. The skin. Everything, until they get out.”

I was sweating profusely, and feeling weaker still, but I had to ask. “And how many eggs does the dragonfly queen lay?”

Patu took a breath before he answered. “Millions.”

I felt faint. I staggered momentarily. He quickly pulled an armchair up and I crumpled into it. I was doing my best to keep from retching, but my mind was racing.

“Patu, a moment ago you said Doctor Jonas learned what he must do, and he did it.

What did you mean?”

“I told Doctor Jonas that the only way to avoid his fate was to take his own life. I told him that if he died before the eggs were laid, the queen would fly from his mouth on the wind of his last breath. The eggs require a living organism.”

My God, I thought, as I stared into Patu’s eyes. Eyes that showed no trace of lying.

Unable to stop myself, I asked, “And if he had not taken his life, what would his fate have been?”

“Far more unpleasant,” was his only reply.

My mind began to whirl like a tornado. Surely there were options, alternatives, there must be something. “I can make myself sick, Patu. I can vomit the hideous thing up.

Get rid of the queen that way.”

“Impossible, she will not leave.”

“I can excrete it. I can do that. Before she’s lain the eggs.

“She will not travel that far before giving birth.”

“An operation. Surgery. I can have it removed.”

“It is too late, I’m afraid,” Patu answered, with what I took to be sorrow, well and true.

“The eggs will have been lain in less that a day. They would have begun to hatch

in another. The process has begun.”

To learn that you are going to die is one thing. We all die. To learn that you are going to be eaten, slowly, from the inside out, is quite another. Tears began to run down my cheeks. I didn’t care.

Then quietly, sadly, Patu said, “There is more.”

“More … my God, man, how can there possibly be more?”

“Once the host is infected with the growing eggs, everything he touches becomes infected. Everything he puts to his hands, his mouth, his loins, even his breath itself becomes a possible host. A host that might eventually breed more queens and more brokenhearted dragonflies. The cycle is like that of the sun and the moon.”

“You’re saying there’s no way to stop it? No way at all? Absolutely nothing I can do?”

“There is one way to stop it,” Patu added, “if one has the courage. If the host is consumed by fire, before the queen flees, then and only then will the cycle be broken.”

Stunned, and still weeping, I blubbered, “Consumed by fire? You’re saying that if I burn myself to death, I may not pass this on to others?”

“Yes.”

Still hoping for something, anything, any reprieve at all from a fate worse than death or at least a death far less gruesome, I said, “Patu, I saw a revolver in the study. If I use it on myself, will you burn my body? And will that keep me from passing on this hideous malignancy?”

“No. The host must be living when the flames consume the dragonflies.”

I was no longer capable of speech. Patu sensed that. He said, “Later tonight, I will put the house to the torch. It must be done. I shall then have to live my own life unsure of whether you have passed this curse to me.”

“My God, Patu, life was just beginning for me. It all seems so senselessly … so cruelly unfair.”

Innocently, he responded, “Fairness is a superstition. A British one, I think.”

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

It is almost midnight. Patu will be lighting his torch soon. I will bury this history in the garden, among the earth and the things that crawl beneath it. Then I have a decision to make. Shall I flee? Shall I roam the world shunning all contact with others while I’m gnawed into oblivion by an abominable infestation of something viler than the maggots that eventually await us all. Or do I go up to the bedroom, lie down and wait for Patu to begin. To be burned alive. To be engulfed in searing flames with my own screams echoing as my ears burn away. To become the fuel for a conflagration that might save others. Am I capable of that? Am I that strong? Am I that good? I honestly do not know.

Which means, neither do you. Reading this, you don’t know whether I chose to live whatever horrendous life I had left, or whether I died roasting in a hell on earth. You don’t know if I kept you from potential harm, or if I passed that harm on to another, who may one day pass it on to you. You don’t know if I left the malignancy on the arm of an antique chair, a shipboard rail, a stack of junk, sitting dormant in a room that you may someday enter.

You don’t even know if the paper this story is written on … the very paper you hold in your hands … is now infected with the scourge of the brokenhearted dragonflies.

But you have only yourself to blame.

You were warned.

Joe Kilgore is an award-winning advertising writer who has plied his trade around the world. Recently he has turned to fiction (as if advertising wasn’t enough) and penned short stories that have been published in the anthology, The Creative Writer, the magazine, Writers’ Journal, and via online literary magazines, RambleUnderground.org, MoonlineMesaAssociates.com, and Bartleby-Snopes.com He currently has a novel entitled The Blunder available via Amazon and Barnes&Noble.com. Joe lives in Austin, Texas with his wife, Claudia, their French Bulldog, Jezebel, two cats and an African Gray Parrot. To learn more about Joe and his fiction, visit his website at www.joekilgore.com.

ISSUE:

S P R I N G

2011

THE NEW

RULES OF

W R I T I N G

By accessing this site, you accept these Terms and Conditions.

Copyright © 2010-2011 TheWritingDisorder.com ™ — All rights reserved