I am a child of the North. The cold is in my blood, and I was born to cherish it. My mother is from China’s Northern Peninsula, and my father is from a small town outside Beijing. Both are solid Northerners. My father tells the story of bringing me home to his mother for the first time when I was an infant. My grandmother, a matter-of-fact petite woman who has birthed seven children and lost two, noticed right away: This child has cold flesh. It’s good for avoiding sickness.

This assessment, it turned out, was only partially true. As a toddler, I captured sickness often. I was prone to fevers and sore throats. I remember the days spent wrapped in itchy blankets, the feeling that the same heat scorching my brain was also evaporating from my eyeballs. I remember my mother forcing me to drink glass after glass of hot water that smelled faintly of metal and fish from the pot used to boil it. I remember agitated dreams, in them the sensation of me hovering above a life-sized cat’s cradle set, my feet floating in and out of the strings and sinking into the squishy ground. Once, within the first year that my mother and I moved to America, I logged a 103-degree fever. My mother called my father at the laboratory where he worked but he did not respond right away. Panicked, my mother bundled me up, put on her winter jacket, and carried me down the street toward the direction of the hospital. My father had received my mother’s message and was driving home when he saw his wife at the side of the road running with a bundle of wool. By the time we arrived at the hospital, my forehead had cooled. I sat behind a speckled blue divider in the waiting room with the nurse’s plastic thermometer under my tongue. It tasted like rubber.

She can still talk. She can still walk, can’t she? The nurse said as the machine beeped with my temperature. 99 degrees. She’s fine.

And then we were sent home. Years later my father told me that we didn’t have medical insurance at the time. My mother did not know this. She still doesn’t.

Once I started elementary school, I never got sick again. My mother said that this was because all the bad heat had burned out of my body. My father said that his mother had been right all along. I had cold flesh. Not cold blood. He said. Cold flesh. He then explained that what his mother—my grandmother—had meant was that according to Chinese tradition, babies with cool skin are healthier than babies with warm skin. They don’t have the internal body heat that eventually turns into sickness and other sorts of bad energy.

What my grandmother had meant was that I was a cool-skinned baby.

One of the lucky ones.

******

The drive from Chicago to Milwaukee is about two hours, a relatively straight shot on I-94 along Lake Michigan. This is the route of my first trip in America. It was the fall of 1990. I was two-and-a-half years old, and had flown with my mother into O’Hare International Airport by way of entry into the country through Seattle. On the plane, I had cried just before takeoff. The flight attendant had come over to where I sat, bent down to eyelevel and examined my seat belt. She had poked around my belly area under the folds of my heavy jacket. My toddler knees hadn’t yet reach the edge of the seat, and I can still see my legs jutting out in front of me, my sneakered feet suspended in mid-air. I had continued to cry and at some point was given a bag of peanuts. I’m told everything was okay after that.

I don’t remember saying goodbye to my grandfather at the airport in Beijing, or walking onto the plane, or taking the picture that would eventually be pasted onto the passport that my mother and I shared. But I remember the peanuts—not eating them but holding the shiny bag in my hands. I don’t remember crying, but I remember others looking my way and the flight attendant peering at me, smiling with bright red lips and speaking in a voice that I associated with women in barrettes and hairnets. I don’t remember being scared or uncomfortable. I guess sometimes children cry just for the sake of it.

When the plane landed, I knew that my father would be waiting for me. I hadn’t seen him in a year, when I was last one-and-a-half, but I sensed that he was getting impatient. I pictured him in his white button-down shirt made of thin cotton, leaning against a wall in the airport, with his arms folded over his chest and one leg crossed over the other. This is how my father stood. Alert, but not nervous.

On the airplane, the long, tired line of passengers lingered in the aisle and moved very slowly. I stood on my seat and banged against the side of the plane. Again, people looked at me. At this point, I didn’t know what Chicago was and I didn’t know what Milwaukee was. I only knew that I was in America. I don’t actually remember knowing this in the moment but I’m told that, in the months before the flight, I had bragged to all my mother’s friends that my father was in America and that I’d soon be on a plane to get there too.

In the fall of 1990, my father lived in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. He had just moved there from Temple, Texas. Both are highly unlikely places for a farm boy from Northern China to be. My father was a child of China’s Cultural Revolution. School was abolished during the years that should have been his freshman, sophomore and junior years of high school. During his senior year, he learned all he could and signed up to take China’s national college entry examination. This was a reckless move, because even students with formal high school educations did not easily pass this exam. For most, failing meant waiting another year to retake the exam, or foregoing college and attending technical school instead. For my father, the consequences of failing would have been dire. He did not have the money or time to waste on an extra year to try again. If he didn’t pass, he would likely have ended up like his brother driving fertilizer trucks for a living.

My father aced the exam. He was famous in his village for a short while. In a series of subsequent maneuvers, he studied in Beijing, was sent to Manchuria for post-graduate research, met my mother there, and then applied for temporary research positions in America. He was accepted to a research fellowship by a professor at a university in Temple, Texas, and so he decided to go. As I am told, my father came to America with one suitcase and one hundred dollars in his pocket. From the pictures, he looked the part with his overgrown black hair, dazed grin, and thick-rimmed glasses.

I don’t know much about my father’s life in Temple. I know of the Japanese roommates and the mistaking of soap for soup, which led to confusing conversations with his Texan boss, but I don’t know much more. Sometimes I even forget that my father had lived there at all. Years later, I went camping in Central Texas with my boyfriend and actually passed by Temple without realizing it. Only afterwards, when retracing my trip to my family, did I realize that I had driven right by my father’s first American home.

My father came to America a year before my mother and I did. During that year, his absence affected me just like his presence would have. From a young age, I had a strong sense of blood lines, and I remember more than anything that I was severely proud of my father. This is a funny thing for a two-year-old to feel. I didn’t even know what pride was, but I embodied it. I knew my father was doing a good thing. I knew that he got to do it because he was smart. I knew that other people’s fathers were not doing it. I liked this very much.

Strangely, I don’t remember missing my father during that year. When my mother and I first got to Milwaukee, I was shy to even speak to him. It took me a few weeks to get over it. In a sense, my father had become a celebrity to me—someone associated with things bigger than my ordinary life. It took time to adjust to living with him, to him being my father again.

In those first few weeks, my father would ask me again and again, are you my kid? The first few times, I was confused by the question and tried to answer correctly.

Yes I am.

Yes?

Yes.

And then I started to sense that he was playing with me. The next time he asked I didn’t give a straightforward answer.

Who else’s would I be? You just like hearing me say it.

And then he laughed sweetly in a way that made me feel good and proud to be his kid.

******

I remember very little of my first trip from Chicago to Milwaukee. I remember nighttime and orange streetlights reflected on slick roads. I remember a vague sense of the world outside being concrete, orderly, sterile, without people. I don’t remember who was in the car with me, if my father had borrowed a friend’s car for the highway drive. I know I must have seen everything from the backseat.

Over the seven years that my family lived in Milwaukee, we made many trips to Chicago. My memories of these trips are shards—generally scattered but each piece bright and sharp. I see flashes of a summer day: the cone-shaped toll machine, me leaning out the back window and tossing nineteen cents into it, the striped bar lifting and us driving through. I see the gray ceiling of our car, me carsick lying across the backseat, my stomach churning with every click of the car tire on concrete slabs. What I remember the most, however, are the monstrous steel roller coasters that came into view about halfway between the two cities.

Four words that got me excited: Six Flags Great America.

My family went to Six Flags once, when I was about four. My parents had saved up for I don’t know how long. I wore a special dress that day, a frilly thing of pink lace. There is a picture cementing this. In it, my father and I sit smiling from under the shade of a picnic table umbrella. The umbrella is whickered, and flecks of sunlight pass through landing on our faces. I am grinning from cheek to cheek, my baby teeth lined up like a row of corn kernels on a cob. A single juice box sits on the table between us next to a gray camera case. My father is wearing his white button-down shirt and his thick-rimmed scientist glasses. His hair is chestnut brown in the sun, and as thick as ever. We have the same shaped face, the same features.

I only went on one roller coaster that day. My father and I had waited on line and followed its zigzag path. We were the last ride of the night. Even now, I have no idea how I was allowed through by the park rangers. I was clearly too young and too physically little to be on this ride. I was aware of the height requirement. The image of a bear in a baseball cap was painted onto the fence by the entry gate. Along the bear were ruler-like slashes with a bold one indicating the required height to go on the ride. I could see that I was just below this bold line. I’m pretty sure my father didn’t see this bear. I was too scared and too excited to say anything about it. I didn’t want to be stopped at the turnstile. It would cause a commotion, which would be incredibly embarrassing for my parents, who didn’t speak much English and avoided confrontation at all costs.

When my father and I were finally at the head of the line, I stared straight ahead and waited for the ride before us to empty out. When it did, I walked forward quickly. Once I was already in the cart, shuffling my way to the last seat across the clunky wooden bench, I knew I was safe. The family in line behind me would already be piling in, and the ride operator would be too busy looking at others to see that I was a head shorter than everybody else. It was already dusk by now.

When the teenage boy with the Six Flags pin on his shirt came by to check our seat belts, I discreetly extended my legs so they would look longer. I gave him what I thought was a cute smile. I don’t even know why I did that. Years later, I would have the same feeling when trying to get past bouncers into bars and nightclubs.

******

In Milwaukee, my family lived in a one-bedroom apartment on North 76th Street, across from a church and a high school. Our apartment was one of eight units in a two-story brick building with patches of wild grass as front and back yards. We lived on the second floor and faced the street. We felt lucky to have a view of the traffic outside.

Like every other unit in the building, ours had a large rectangular window in the living room. The window came with built-in shades—an off-white plastic sheet that rolled down manually from a horizontal rod above—but we never used it. For a long time, we didn’t realize that the world outside could easily see us, especially at night. Only after my parents’ friend told us that he could see us eating dinner around a desk in the living room every night when he drove by did we begin pulling down the plastic shade at night.

We lived in that apartment for seven years, during which my father completed his PhD in biochemistry and my mother completed nursing school at Milwaukee Area Technical College. In China, my mother had been a middle school grammar teacher, but there was no future for her in that line of work once we were in Wisconsin. So she changed careers entirely and threw herself into mastering English and becoming a nurse. She would sit at the table against the wall in the living room every night with her thick textbooks, one elbow set on the table and her head propped in her hand. Often her eyes would be closed, memorizing and concentrating. Soon after my mother entered school, I was told that she needed quiet time to study and that we no longer could play like we used to. I stood by the giant window across the room, looking back and forth between the street and my mother.

I shouldn’t talk to you, right?

Usually she’d be too deep in thought to hear me.

******

I had friends in elementary school, but almost all of them were only school friends. They were not good friends, meaning I never saw them outside of school. Only one friend ever came to my home. Her name was Sarah. Sarah had moved to Wisconsin from Syracuse in the third grade, and was an outcast for much of that subsequent year. I was one of the kids to initially bully her, because she was overweight, buck-toothed, had a boy’s haircut and spoke with a strange accent. We eventually became friends.

The summer after fourth grade, Sarah and I spent a lot of time together. For the first time in my life, I had somebody American to call a good friend. When Sarah and I saw each other outside of school, it was almost always at her house. She lived in a two-story colonial in Brookfield, a nearby suburb of Milwaukee. Her house was amazing to me, in large part because there was a staircase that overlooked the foyer. I had only seen this before in houses from movies. Sarah and I would walk down her street and climb the grove of pine trees that grew on a grassy island deep in her development. We had sleepovers and watched Grease while lounging on the black leather couches in her living room. Her two older brothers would come in and out of the room, and I thought it was so cool that she wasn’t an only child. Two years later, I’d have a younger brother of my own, but I didn’t know this at the time.

That August deep in the summer of 1998, I moved away. The last time I saw Sarah, her dad had driven me from her house in Brookfield back to my apartment in Milwaukee. Sarah had never seen where I lived before. We pulled up to the front of my building and my father came out the front door and invited everybody upstairs.

We didn’t have proper chairs. Sarah’s dad sat on a plastic pink stool. He was a big man with a mustache and beer belly, and he just sat down on the pink stool with his legs folded under him like it was the most normal thing in the world. I showed Sarah around the apartment. We walked from the living room and into the bedroom, past the bathroom. In the bedroom, she asked, this is where you sleep? I nodded. We looked at the queen-sized bed that I shared with my parents. We then walked into my kitchen, a space barely large enough for us to stand in without bumping into each other. The image still burned in my memory is that of Sarah standing in the middle of my kitchen, lit by the single lightbulb hanging from the ceiling. Behind her, I see the tin pots that my parents used to cook delicious things like dumplings, pigs’ feet, or miscellaneous stews. A damp wooden spoon hangs from the handle of a pot. Sarah could have touched the walls on both sides. She could have reached out her arms and stirred the pot with the spoon with one hand while flicking off the light on the other side of the kitchen with the other. Sarah stood there, looking back and forth. Her eyes were wide, and I saw her mouth open and close saying, Wow.

******

I’m sure my parents thought a lot about money, but I rarely did. It was only many years later, after I had graduated from college, when I realized that we were poor. Of course, I had not believed my family was rich either. I just didn’t know we were poor. I was aware that money could buy things, and that we couldn’t buy many things, but I didn’t think much about it. We were what we were. I was blissfully ignorant in this way. I remember once losing a pair of gloves and feeling regretful because instead of buying a new pair, I just didn’t have gloves for a while. It didn’t occur to me that someone else could go to the store and pay for another pair of gloves.

When I was growing up, my mother worked odd jobs as a waitress at a few Chinese restaurants and a cleaning lady at a Howard Johnson motel. I don’t remember ever thinking about what other mothers did for a living. One time, my mother responded to a flyer for a “work at home” job making beaded earrings. My father had seen the flyer, a loose sheet of paper stapled onto a telephone pole, while he was stopped at a traffic intersection.

My mother had nimble fingers. They were long and precise, like those of a concert pianist. For a few weeks after she graduated from nursing school and couldn’t find a job, she sat hunched over a table at night threading little black and white beads just as depicted in the all-important instruction manual. The earrings she created were beautiful, impeccable, exactly as shown on the brochure, but still they were never good enough. My mother would mail out a package of earrings, only to have them all returned with some disqualification. The problems were invisible to my father and me—the fifth row was not aligned properly; one of the dead fringes was stringed too tightly so that it couldn’t dangle correctly; two earrings didn’t match perfectly as a pair. My mother gritted her teeth and tried harder, worked more carefully, longer into the night. But still her product was denied. It took some time for my parents to realize that they were being scammed. They had paid money to buy the instruction manual, the beads and thread in the hopes of earning it back, plus more. We would never get that money back.

******

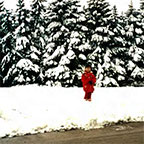

Wisconsin is a blessing to me. What I have are the good memories. I remember snowy days ice skating on frozen ponds, and being the only one there. I remember walking on thin sheets of ice atop snow on the fields outside my elementary school. I was small and light, but not weightless, and when I eventually fell through the thin ice, the snow came up to above my head. I remember climbing on enormous piles of snow that had gathered at the edges of parking lots. The piles were shaped in strange circular heaps from the snow plow, like sloppily scoped ice cream. I remember beautiful evergreen trees decked with patterns of white. I remember sitting with my father on a sled and flying down a hill toward the bottom where my mother stood watching and waiting for us. I remember at some point when I was pulling the sled back up the hill, I lay down on the hard ground on my back. I let my limbs relax. I stared up at a clear blue sky, hearing the squeals of other sledders around me. I remember being so happy, so at peace, thinking that this was how I wanted to feel on my wedding day.

Many times during my grade school years, my father and I waited in morning blizzards at the corner of the alley for my school bus. We stood facing away from the snow and let the feathery flakes slash through the sky at our padded backs. We played games, quizzed each other on the multiplication tables, jumped and stomped around to keep warm. My father told me stories from his childhood, of him walking to school barefoot miles each way. They always took off their shoes during these treks, even in the winter, because they did not want to waste their soles. The rule was one pair of shoes every two years, if lucky. My father told me stories about the kids in his village, of them waiting for the odds and ends from the local butcher, and then blowing up pig bladders to use for kickball.

During those cold mornings, my father never complained. He kept the conversation going even when my bus was thirty minutes late and he already should have been at work. Later, I realized that he must have really enjoyed telling me those stories. Yes, he told me the stories so I could learn about where I came from. But more than anything, it was his way of reliving a life that was far away and long gone.

It’s a strange thing, to grow up. It’s an illusion. You keep your eye on it for the longest time. You track your birthdays, your years in school, your height in pencil marks against the kitchen wall. And then, inevitably, you lose track of things and that’s when you find yourself on the other side. For the longest time, I was growing up. Growing up. Still growing up. And now I am suddenly grown up. My childhood is a flash that has somehow passed through me, like a ghost or a pale breeze. My childhood is not only over; it is solidified. It is completely mine and labeled as such. Now I’m the one telling stories.

J.D. Lynn was born in Beijing, China, and grew up in Wisconsin and on Long Island. She is now a lawyer living in New York City. She writes fiction and creative nonfiction, and composes songs on the guitar and ukulele. This is her first publication.

ISSUE:

W I N T E R

2013-14

SUPPORT THE ARTS

DONATE TODAY

GET A FREE T-SHIRT!

By accessing this site, you accept these Terms and Conditions.

Copyright © 2010-2014 TheWritingDisorder.com ™ — All rights reserved