David Cowart writes about very specific things, like contemporary American fiction. When you read one of David’s books you realize that he is passionate about his work, and that he is very passionate about one contemporary American author: Thomas Pynchon.

David currently teaches at the University of South Carolina, where he is a Louise Fry Scudder Professor and a Board of Trustees Professor. That’s his day job. The rest of the time he’s writing about what he loves most — contemporary American authors like Don DeLillo, Thomas Pynchon and Richard Powers.

Here is Part II of our interview with David Cowart.

DAVID COWART INTERVIEW — PART II

The Writing Disorder: Thomas Pynchon attended Cornell University, correct? And he allegedly took a class with Nabokov?

David Cowart: He went to Cornell, but the story about his taking a class with Nabokov has been called into question. The old anecdote about Nabokov’s wife, Vera, remembering Pynchon’s distinctive handwriting hasn’t been substantiated. The course was Masters of European Fiction, which the students called Dirty Lit, because the syllabus included Ulysses and Madame Bovary—perceived as pretty racy stuff at the time. My impression is that certain individuals have seen Pynchon’s transcripts, yet no corroboration of such a direct encounter with Nabokov has been forthcoming.

Charles Hollander confirms, though, that Pynchon did cross paths with M.H. Abrams, editor of The Norton Anthology of English Literature. In an eighteenth-century course taught by Abrams, Pynchon wrote a paper comparing Rasselas by Samuel Johnson to Candide by Voltaire. The two sentences at the end of this paper stayed in the teacher’s mind, and he would quote them to later students: “Like Candide, Rasselas ends on an imperative note: again, to submit; but above that, to endure. It leaves us with less hope than Voltaire, but with more determination.”

There are other Pynchon stories in various quarters. I have long thought that Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up to Me, by his Cornell classmate Richard Fariña, offers a droll picture of Pynchon as the character Heffalump. Jules Siegel, another Cornell classmate, wrote a tell-all in which he accuses Pynchon of running off with his wife. A less sensational romantic attachment was with Anne Cotton, a woman he dated when he interrupted his college education to do a two-year hitch in the navy. She later became registrar at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. I had a nice correspondence with her, but it ended shortly after she mentioned having some letters from Pynchon that she would send me. She probably got in touch with him, and he told her not to deal with these publishing scoundrels.

TWD: Do you see Pynchon more as a writer for men than women?

David: There’s some preference on the part of male readers, and there’s probably a slight preponderance of male students who opt to write about Pynchon’s fiction. But I see a large amount of scholarly work on Pynchon being produced by women critics — Stacey Olster, Molly Hite, Deborah Madsen, Inger Dalsgaard, Kathryn Hume, Tiina Käkelä-Puumala, N. Katherine Hayles, Elaine Safer. I think that Pynchon is sufficiently sensitive and sufficiently resistant to a logocentric or phallocentric or patriarchal narrative (to indulge the jargon for a moment) to commend himself to a complete spectrum of readers. Pynchon really is a man for all tastes.

And that includes foreign tastes. Even abroad, Pynchon enjoys something like cult status, and scholars publish on his work in Australia, New Zealand, Malta, Belgium, Germany, Poland, Finland, Sweden, Denmark, Switzerland, Japan, Russia, Korea, China, Italy, France, Spain, and England.

TWD: Have you ever encountered Pynchon fanatics who were women?

David: Well, maybe not real Pynchon maenads meriting comparison with the King Kong Kultists in Gravity’s Rainbow (lawn-party-on-the-birthday, name-their-children Benny and Zoyd, Friends-of-Thomas fanatics), but I’ve encountered some pretty enthusiastic women readers of Pynchon. They’re the ones with whom I swap book recommendations that are well received on both sides.

I have a list of books I like to recommend when people ask. Things like Goodbye to All That or I, Claudius by Robert Graves. The Gold Bug Variations by Richard Powers. There’s Tolkien, Kesey, Michael Ondaatje, Rosemary Sutcliff, Chang-rae Lee. I like Octavia Butler, too, the only true science fiction author that comes to mind as recipient of a MacArthur grant. I respond most passionately to books that are truly well written, regardless of their standing as serious literature. That’s one of the things one learns when reading Pynchon. There really has been a coalescence of popular and highbrow forms. When Inherent Vice came out, I was struck by the blogger who wondered: “How is this different from Elmore Leonard?” And recently, reading the wonderful thrillers of Don Winslow, I’ve had the uncanny notion that this was Pynchon, writing under a pseudonym. Same wit, same mordant locutions, same California setting, same distrust of what Adam Levin, in his mammoth messianic fantasia The Instructions, calls the Arrangement (Kesey and Burroughs had their own names for the monolithic forces of respectability and conformity).

Pynchon has, of course, appropriated and interwoven and hybridized various fiction forms. That creative eclecticism, after all, is one of the characteristics of the postmodern aesthetic, that chipping away at the distinctions between high culture and popular culture.

That said, I am myself old-fashioned enough not to want to discard all such distinctions—this postmodern premise can be overdone. I like to invite the doctrinaire to consider the desert-island challenge: if they could take only one book into lifelong exile and it had to be either Finnegans Wake or, say, a novel by Neal Stephenson or Stephen King, which book, I ask, if it’s all they’ve got for the rest of their days, would be worth reading and re-reading? A variant of the question is aimed at those who deny the intrinsic difference between a work of the imagination and a work of criticism or theory: would your desert-island book be something by Jacques Derrida, admirably complex and challenging, or would you rather have Gravity’s Rainbow, admirably complex and challenging in a significantly different way? Me, I’d rather have—hands down, always, every single time—a work of the imagination that subordinates the big questions to sheer readerly exhilaration. As Nabokov said: “good books should not make you think—they should make you shiver.” The narrator of that Adam Levin novel I mentioned a moment ago iterates this sentiment: “books with lessons are bad books.” Not that one dispenses altogether with the traditional Horatian counter-weighting of delight with instruction.

TWD: You’ve written about Chuck Palahniuk’s work as well.

David: I wrote a piece about his 2001 novel Choke (it will appear presently in a Continuum volume on Palahniuk). I’m not really a big fan, but he’s certainly a clever writer, and he has articulated some of a generation’s strong feelings of yearning, outrage, betrayal. You remember Tyler Durden’s remarks in Fight Club:

“We are the middle children of history, raised by television to believe that

someday we’ll be millionaires and movie stars and rock stars, but we won’t.

And we’re just learning this fact . . . So don’t fuck with us.”

Tackling Choke, I discovered a good deal of substance–it stands up well to analysis. I just don’t feel, from page to page, that I’m in the presence of a great, humane writer. Nor, as Lev Grossman has observed, is there as much latitude these days for a writer to become the voice of her or his generation (I speak as a member of the generation that came of age in the sixties).

Early on, it’s Fitzgerald and Hemingway. Then it becomes Burroughs or Ginsberg, then Kesey or Vonnegut or Heller, then Pynchon or DeLillo. But it’s less and less easy now to emerge as the recognized voice of one’s generation. As a society, we’ve become so multifarious, so different, so heterogeneous. What we have now are the various voices of gender identity and political identity, immigrant voices, geriatric voices, voices of environmental consciousness. The voices resist coming together in concert—and that’s probably not a bad thing. Nor does any of this preclude discovery of the voice that speaks to you and the others who share your outlook and taste. That’s one of the pleasures I find in reading Pynchon, and it’s what keeps me sampling his successors.

I do think that for a long time now we have recognized a cadre or phalanx or generation of writers whose excellence tends to dim the luster of younger practitioners. Nevertheless, my next big project is to think seriously about a post-DeLillo, post-Pynchon generation. The great authors born in the 1930s (Barth, Barthelme, Gardner, Phillip Roth, Toni Morrison, DeLillo, Pynchon, Cormac McCarthy) have consolidated the postmodern aesthetic crafted by their slightly older cousins: Gaddis, Heller, Ginsberg, Vonnegut, Flannery O’Connor, Grace Paley (all born in the 20s). You have these really titanic, powerful figures who continue to be productive, continue to pop your eyes open in various ways. Cormac McCarthy has gone through several incarnations already.

So I want to know what’s on the horizon. What’s being brought to the novel, to storytelling, by writers born in the 40s or 50s or 60s—or, like Jonathan Safron Foer, Allison Krause, Dave Eggers, and Nathan Englander, the 70s? Are these younger writers consolidating the aesthetic crafted by the generation born in the ‘20s and ‘30s? Are they contesting it, reversing it, turning it upside down? David Foster Wallace was frequently quoted to the effect that he meant to return to a place of sincerity, to rethink some of the relentless irony of both the modernists and the postmodernists. But in fact, if you look at what he wrote, it seems to me that he is on that same postmodern spectrum. What I’m suggesting is that postmodernism is an aesthetic that has staying power. It’s not universal (there’s still a whole lot of perfectly respectable realist fiction being written), but if we’re looking for something that represents a sustainable tradition, then postmodernism may just be getting started.

But it gets tricky, trying to imagine the future of American fiction. I do think, for what it’s worth, that Richard Powers is one of the strongest writers of this younger generation. David Foster Wallace is very good, but—

TWD: I sometimes got the feeling that David Foster Wallace was overwhelmed by his own talent and abilities.

David: Yes, that’s nicely put: his brain must have been like one long Terry Gilliam movie. But how awful the admixture of crippling depression. The Wallace story is terribly sad—the sadder for our hearing so belatedly about the psychological burdens he bore. Not waving but drowning . . . .

Wallace corresponded with Don DeLillo—I’ve just been reading a dissertation devoted to DeLillo as literary mentor (it’s by Dawson Jones). But even as he sat at DeLillo’s epistolary knee, Wallace sought, with only limited success, to free himself from the looming shadow of writers like DeLillo and Pynchon and Barth. He evidently knew Barth’s work and learned a good deal from it—even as he self-consciously parodied any actual apostolic relationship (I’m thinking about his ludic treatment of the character Ambrose (obviously Barth) in “Westward the Course of Empire Takes Its Way.”

TWD: Returning to Chuck Palahniuk. I’ve worked with three women (one an editor, one an assistant editor, and one an editorial assistant) who were somewhat fanatical about his work. They had read everything he had written (or nearly everything), gone to numerous book signings, and also paid to see him read his latest work. I’m just wondering what your take is on this writer’s having such a devoted following among women?

David: I’m happy to hear that a youngish writer (well, no longer so very young—he’s fifty now) is generating such passion on the part of readers. It’s one more rebuff to those who keep pronouncing the novel dead. It’s not. It may be moribund (no genre is immune to time and taste), but its funeral plot need not be purchased any time soon. It’s good to hear that there are writers out there who can generate that kind of passion.

TWD: So who influenced Thomas Pynchon as a writer?

David: Easier to say what he has read. From the evidence of his own allusiveness, I think he is very widely read, as only a polymath can be. He knows his Jacobean drama, his Emerson, his Henry Adams, his Rilke, his Eliot, his Orwell. He delights in popular writers such as John Buchan and Alfred Bester. If he’s faking his knowledge of German, Spanish, Russian, Japanese, Serbo-Croatian, and Afrikaans, he’s doing a hell of a job of it. Whether in translation or otherwise, he has read a good deal of German and Spanish literature.

As for influence, per se, he has revealed a little about certain writers he took to early on—or came to respect. Some were formative. He came of age in the 1950s, a time when there was a lot of talk about conformity and a lot of anxiety about external influences and forces. This was white bread America; this was the conservative, unimaginative, Eisenhower era. And suddenly, like a bombshell, burst Norman Mailer, burst Allen Ginsberg, burst The Evergreen Review, burst Playboy magazine—all experienced by sensitive souls like Pynchon as liberating influences. They spoke to some visceral hunger on the part of the intelligentsia, and Pynchon was among the most famished.

TWD: You’ve written about John Gardner and his fiction. For me, John Gardner is better known for his books about (writing) fiction.

David: On Moral Fiction, for example, or On Becoming a Novelist or The Art of Fiction. Yes, and I salute you for being aware of them. Because he has entered the penumbra that awaits even good writers who have exhausted their fifteen minutes of fame, few people pay much attention to him now. Yet we might do well, still, to resurrect his dissenting voice, which is what comes through powerfully in On Moral Fiction. He made a mistake in that book, in that he named some names and seemed to be patronizing or disparaging some of the really important writers of his time. But he made a legitimate point, which was that we become what art says, what it shows us, what it says that we are. His homely example was that, growing up himself, he and his friends went to a lot movies and saw various charismatic actors smoking, so they all did that, and they all got cancer. He did so literally. Thus he strove in his work (and he is quite emphatic about this), to depict behaviors worth imitating among characters who are (or come to be) models of virtue. He wanted to present characters determined to rise above existential circumstance—and he glorified artists (I think of Vlemk the Box Painter or, more obviously, the Shaper in Grendel) whose idealizing depictions call real-life counterparts into existence. Gardner’s idea is that an affirmational art will find its mirror in a larger cultural resurgence. He says for a long time now (certainly throughout the twentieth century), we’ve been getting nothing but the existential bad news from our artists. The Waste Land, so relentlessly bleak, is the foundational document of the age. If what you’re getting from art are endless variations on this theme, it’s not conducive to spiritual optimism, to purposiveness — to the idea that life can be made better. Cumulatively, such art fosters the growth of a healthy culture, a robust civilization. Gardner liked to contrast the art produced in the Renaissance or in Periclean Athens with the art produced in modern times, especially in the twentieth century. It’s a telling point, and it brings us back to the question, what do we want art to do? Do we want it only to tell us, as rigorously as possible, the truth? We do expect art to be honest about the truth, however dark and bleak and painful, but Gardner resisted that conception of art because it slays no dragons—or, rather, it promotes the slaying of no dragons. We all know that no one can defeat a dragon, but heroes, who learn their trade from heroic fictions, nevertheless do so. Gardner was by training a medievalist. He read and taught and wrote about Beowulf, whose protagonist is a model of heroic virtue — a figure who embodies values that shaped the English-speaking world for centuries. Gardner was looking for ways to recover the kind of vision that animates the Beowulf poet. He wrote this absolutely brilliant book, Grendel, which is Beowulf from the monster’s profoundly wrongheaded point of view. His relentless debunking of events in ancient Scandinavia notwithstanding, Grendel is king of the unreliable narrators. He’s recognizable, if you listen, as a parodic version of the modern or contemporary writer who, understanding the absence of any supernatural comfort or prospect, dwells on the bleakness and the harshness of human existence. Grendel says, “I know, I know the truth, I know reality, I was there. I saw the ridiculously inglorious beginnings of the human struggle.” Yet in the end he is bested by a hero who exists, paradoxically, only in a poem. Heroic narrative spawns its own instantiation.

It’s Beowulf who, defeating Grendel, is a hero, but he is a hero at a remove. The one who really triumphs over Grendel, the one that Gardner ultimately shows as having wielded the positive and benign power of art—is the Beowulf poet, the Shaper. Gardner and the Shaper say it’s the responsibility of the artist to cultivate what Keats called negative capability. Great artists may know there is no hope in the world yet still believe that if they keep telling hopeful stories, well, hope comes about.

I still teach Grendel almost every year, it’s the one Gardner book that is perfect: it’s short, accessible, entertaining, funny as hell.

In that he appropriates and retells an older story, Gardner is an exemplary postmodern. What Borges talks about in “Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote” is paradigmatic of the enterprise in this late phase of our culture in which artists are obliged to appropriate material from prior artists, then recapitulate, rename, retell it. We used to have this shibboleth about originality on the part of the artist. In fact, in no era is that quite an accurate account of what goes on in artistic creation. But more and more in our time, art is symbiotic, and artists are quite frank about their reconfigurations of prior art. Hence Smiley’s A Thousand Acres, which is King Lear on and Iowa farm in the 1970s. Or Jean Rhys’s Wide Sargasso Sea, which reframes Jane Eyre, or that strange rewind of Robinson Crusoe, Coetzee’s Foe, or Stoppard’s Rosencrantz & Guildenstern Are Dead. As Gardner appropriates and turns Beowulf inside out, Stoppard appropriates Hamlet and turns it on its head, makes it the vehicle of a meditation on our benighted era. It turns out there’s a lot of this kind of thing going on, and it seems to be highly characteristic of postmodern imagining and storytelling—or, to borrow Joyce’s pun, stolen-telling.

TWD: And Gardner had an influence on Raymond Carver’s work.

David: Yes, Gardner was his teacher and mentor—Charles Johnson is another who benefited from Gardner’s generosity. But I don’t think Carver ever managed fully to embrace the moral fiction or affirmational frame or outlook that Gardner advocated. Which is as it should be. We don’t want people to enlist under the banner of John Gardner or any other writer. From time to time they cross paths with or learn things from certain writers and go on to imagine freshly and, as Julian Barnes once said, knit their own stuff. The paradox is that no one actually invents ex nihilo.

TWD: Have you ever written any fiction?

David: I wrote a novel. Back when I was in the Army, I was a radio and television broadcaster. We were all flipping coins to see who would work during a holiday, and I said I will work all holidays and all weekends if I can work only three days a week. When this was accepted, I had some spare time, especially since I was stationed in Panama, and nobody was shooting at me. So I wrote a novel based on my Peace Corps experience in Ethiopia: I imagined myself in the midst of an uprising or revolution. It was a good exercise. This was before I attempted a dissertation or a scholarly book, and it taught me how you might sustain a lengthy piece of writing. Nothing ever came of that novel. For a while I sent it to around to publishers. On one occasion, it came back thicker than it left. And I thought, wait a second, what is this? It had been packed with another rejected manuscript—a bodice ripper by a man writing under a woman’s name. So I repacked it and sent it on. I eventually had my typescript bound for posterity. Qualis artifex pereo!

I sometimes think that I will never retire, but if I ever do, I might make another attempt at fiction. I sort of decided that I could do one thing reasonably well, but probably not two things. Like the hedgehog and the fox, you know? The hedgehog does one thing well and the fox does many things. I was always a hedgehog and contented myself with scholarly writing about the creative work of others. Since I only write about books I like, I don’t feel like a parasite, draining precious bodily fluids from the literary host. Our relations are symbiotic or mutualistic, like the crocodile and the Egyptian plover. I batten on them, and they derive some modest benefit from my ministrations.

TWD: Are there other writers in your family?

My mother wrote some things. After her death last year, I found some rejection slips from Redbook and other glossy magazines. Both of her sisters, my aunts, tried their hands (a romance novel, a short memoir). I also have an uncle who has published extensively on ecclesiastical history. My sister is a freelance medical and educational writer. My daughter, who is a prodigious reader, will one day erupt, volcano-like, in prose. My wife has published scholarly articles on academic libraries and librarianship. My father wrote a memoir about his experience in World War II, called Green Bars. He claimed he had a falling out with his commanding officer and never got promoted, so his second-lieutenant brass bars gradually turned green. It’s immensely interesting and entertaining in an unself-conscious way. Also harrowing (he flew forty-four missions in a B-26). He doesn’t obsess about his prose, but he has an instinct for clarity, rhythm, balance, directness, and economy that I wish I could inculcate in my students.

So yes, there are or have been other writers in my family. The grandparents didn’t write, but they recited. I sometimes wonder about the extent to which my own literary sensibilities were shaped by dinner-table recitations of “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard” and “The Deserted Village” and “The stag at eve had drunk his fill / Where danced the moon on Monan’s rill.”

TWD: Pynchon is now in his seventies.

David: Yes—he was born in 1937, so he is now 75 years old. He and his great contemporary, DeLillo, were born less than a year apart.

TWD: What are your expectations of him in the coming years?

David: One wonders whether he might not, like Shakespeare, pass into a gentler, resigned, less angry phase. Probably not. I do think he will be productive for another decade at least. Saul Bellow was writing worthwhile books right up to the end (not to mention producing children—he had a daughter when he was in his eighties). My perception of Pynchon is that he has passion still—something of the savage indignation that lacerated the heart of Jonathan Swift. There’s so much now to be indignant about, angry about, and royally pissed-off about, especially if you have the instincts of a satirist or a person who has a fairly passionate idea of how things ought to be.

One of Pynchon’s convictions is that American Promise got sidetracked. He recurs to the idea of a malign switchman or “pointsman,” some mythic figure who at a certain point shunted American culture onto tracks more plutocratic, less tolerant. There’s a fine passage in The Crying of Lot 49 in which the heroine, Oedipa Maas, wonders what became of the possibilities, once so great, for diversity. How, she asks, had it ever happened here—so much disenfranchisement, such unconscionable concentration of wealth in such a small number of hands? Pynchon is passionate about this. And I think he will continue to be exercised by the spectacle of American public lives and American politics — American appetites — these are things he will continue to scrutinize, represent, subvert, and satirize.

He writes about the sixties in his three California novels, which are sometimes patronized as palate cleansers between the heavier fare of his large-scale fictions. He alternates the big, ambitious, thousand-page, door-stopper novels with more modest books set in (or oriented to) the 1960s, which he views as the American hinge decade. When in Vineland he returned to the ground already covered in Lot 49, people thought, leave this behind, the sixties are over and done. Now we understand better, having read a third California novel, Inherent Vice, that this is a sustained effort, a roman fleuve, an analysis of the decade in which the country awoke to some imperatives having to do with racial justice and our calling in the world. We awoke to those very important considerations, we briefly embraced them, then—well, it’s like that poem by Salvatore Quasimodo, “Ed è subito sera.” Suddenly, it’s over. Overnight all the anarchic young folks became business majors. I was there for it, I remember. I managed to dodge that specific fate. There was a time when our students gravitated to the humanities. Now university administrators are closing down whole departments of philosophy, classics, foreign languages.

TWD: What about nonfiction. Do you think Pynchon will ever write a book of nonfiction?

David: Well, his occasional nonfiction pieces are much scrutinized and will no doubt eventually be collected. They are quite helpful in thinking about and reading Pynchon’s stories and novels. His essay “Is it O.K. to be a Luddite?” is an ideal companion-text to Mason and Dixon. So while he has not undertaken a long work of nonfiction, when he does weigh in with a book review, a sketch, or an essay such as the one he wrote on the aftermath of the Watts riots, one is intrigued to hear him speaking in what one takes to be his own voice (one can of course hear that voice in a more literal way in those two Simpsons episodes in which he voices a character based on himself). From time to time, he will write a book review or liner notes for a CD or a comic sketch (the one on sloth is especially charming) or an introduction to someone else’s book (a Barthelme collection, Jim Dodge’s Stone Junction, reissues of Orwell’s 1984 and Fariña’s Been Down So Long). He does such nonfictional writing with some frequency.

TWD: And his introduction to his short story collection.

David: Oh yes, Slow Learner, very significant. In that essay (especially important to answering your earlier question about Pynchon’s influences), you can almost see him with a deck of cards, sort of like W.C. Fields, being cagey and laying down personal information cards for the ardent to pounce on.

TWD: What is your own approach to writing? For instance, when you started your new book, how did you begin the process?

David: I used to do a first draft longhand, with a fountain pen my grandmother gave me in 1965. More and more, though, I compose at the keyboard.

The new book (my second on Pynchon) is a bit of an anomaly. I have characterized it as a kind of diary, because it includes material that goes back maybe thirty years. After Gravity’s Rainbow came out, I always tried to write something about new work by Pynchon as soon as it appeared. So I gathered up all of those essays, thinking they might naturally turn themselves into a book. They didn’t. Turns out, you have to provide quite a bit of cartilage, and you have to update, and you have to revise, revise, revise. Fortunately, a central idea was there all along, in Pynchon’s emphasis on history.

More commonly, I begin a book with an interesting problem or question. For instance, the book I wrote on immigrant writers was conceived just after 9/11. Might we not discern in the perennial dream of the immigrant something to restore spirits bruised by so much hatred? Thus I came to write against the academic grain. Immigrants are supposed to be victims of our racism, our meat-grinder economic institutions, but I found novel after novel with a refreshingly sanguine take on the New World and its promise.

I usually try to write a speculative, introductory kind of essay, which I know will have to be revisited once it’s been buttressed by a series of chapters. But that speculative essay is a useful document for trying to get a grant or sabbatical or other support.

Next I look for texts I think exemplary—and particularly compelling to me personally. In the immigrant writers project, I was delighted to find plenty of highly polished, completely literary works of fiction by a wide range of the recently naturalized—Bharati Mukherjee, Lan Cao, Ursula Hegi, Edwidge Danticat, and the amazing Chang-rae Lee, whose first two novels, Native Speaker and A Gesture Life are simply stunning. The latter is a lesson in how to render experience remote from your own. Since The Confessions of Nat Turner (attacked for its putative appropriation of an African American life), authors have been wary about representing the sexual or racial other. Lucky Shakespeare wasn’t subject to any such proscription. In A Gesture Life, Korean American Lee imagines the story of a Japanese immigrant with a dark secret: during the great Pacific war, he was a medical officer responsible for keeping hapless Korean sex slaves healthy enough to serve the imperial army. It’s the decent but self-deceiving Japanese American who narrates, and Lee contrives for his representations of Korean and other women—three in particular—to be tragically impercipient.

It’s always an investment of about six to eight weeks to write about a book at chapter length. At first, it’s just staring at the blinking cursor, but then it begins to quicken. I’ve learned that if I will simply write something, simply put some words on the page, no matter what they are, I eventually stumble across matter that will nudge me, something I can expand or modify. When I get really stuck, I just go through and start tidying up egregiously bad sentences—even though what’s in them will eventually make its way to the dustbin. You do this long enough, and two or three neurons return from wherever they’ve been malingering. In my case, the process leads to discoveries. When you immerse yourself in the process, ideas eventually present themselves. I do enjoy the phase in which, as things come together, the work becomes pure obsession, and draft after draft from the printer suspires.

TWD: Do you write every day?

David: Not quite, but I’m a great believer in the nulla dies sine linea precept. It’s good counsel, but often other responsibilities intervene. For a while I was a single parent, and, believe me, that’ll put a crimp in your work day. And the teaching, of course, takes lots of time (and it should). Mostly, one writes in the summer, but I’ve learned not to wrap up a difficult chapter before school recommences in the fall. Better to have something well under way by August, then you can keep working on it through the fall semester. Same process over the winter holidays: get something going, finish it up over the spring.

TWD: Anything else in the pipeline?

David: I just finished a short monograph, a reader’s guide to The Crying of Lot 49. It’s a kind of vade mecum for general readers and students who are writing about this book.

TWD: Pynchon includes in his books lyrics for imaginary songs. Some of the funniest are in Lot 49.

David: That’s one of his most charming innovations—his characters will simply stop what they’re doing and perform a little song. It’s always surprising and engaging—and often utterly hilarious. The best ones are in the first three novels—there’s a slight falling off when we get to Vineland. But the lyrics in V., The Crying of Lot 49, and Gravity’s Rainbow are wonderfully mnemogenic (I thank thee, Volodya, for teaching me that word). You find that you have memorized them without trying:

There was a young fellow named Hector,

Who was fond of a launcher-erector.

But the squishes and pops

Of acute pressure drops

Wrecked Hector’s hydraulic connector.

I’ll spare you “The Penis He Thought Was His Own.” There have been a couple of—alas, rather untuneful—attempts to set Pynchon’s wacky songs to music. He himself actually worked on a musical, “Minstrel Island,” while he was in college. Perhaps it was in the back of his mind when he imagined, in Vineland, the ninja Ordeal of the Thousand Painful Show Tunes.

TWD: What is the version you know of Pynchon’s winning the Pulitzer Prize — or actually, not winning it?

David: A panel of judges had chosen Gravity’s Rainbow, but a supervisory body vetoed the award, claiming the novel was immoral and “turgid.” If you look up Pulitzer fiction awards by year, you’ll see a blank for 1974. Gravity did, however, win the National Book Award that year. He later received other awards that he declined (though he accepted the five-year MacArthur Foundation grant). The Pulitzer Prize fiasco remains one of the great embarrassments for American letters. The culture of book awards has gotten, it seems to me, more and more questionable. We want them to be meaningful, and we watch for the announcements. But some of the choices are absolutely off-the-wall or ridiculous. Toni Morrison may be the last American author to win the Nobel (and, honestly, it ought first to have gone to Pynchon, DeLillo, Cormac McCarthy, or maybe Margaret Atwood). The Mann Booker Prize, on the other hand, is still one to watch. The award nearly always goes to a truly distinguished book.

TWD: You’ve talked or written about more contemporary writers like Richard Powers, Octavia Butler, and Stewart O’Nan.

David: It’s part of an ongoing quest to find some real staying power, some genius, somebody who over the course of a career can do something comparable to what Henry James or John Updike, or, now, DeLillo, Pynchon, or Cormac McCarthy has done. And as the culture shifts away from the novel as a prized and honored form, it may be inevitable that we’ll see fewer truly great novelists. Or, worse, great new works of fiction will meet with complete indifference. On the other hand, maybe we just have to enter a small hiatus before we see the emergence, again, of someone who will truly move us as some of these writers have. As I said, Richard Powers does seem to do that.

TWD: Which books by Richard Powers do you recommend?

David: The book that sent me into orbit is The Gold Bug Variations. It’s not quite as demanding as Gravity’s Rainbow, but it’s challenging, at well over 600 pages. His mind is so extraordinary and his command of the medium leaves you in a state of wonder—the way John Barth used to do (before he became too precious). Incandescent prose is something one values, and there is a remarkable command of history, emergent technologies, and science in its many manifestations. The Gold Bug Variations is a beautiful, powerful book, but not a particularly easy one. The book that one ought to start with is the highly readable and moving Galatea 2.2, which resembles Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein in interesting and unusual ways. The Echo-Maker is also engaging. The other book that I particularly admire is Operation Wandering Soul, but I wouldn’t urge anyone to start with that one.

I will certainly treat his work in my next critical effort, this book on the Tribe of Pyn—the younger writers influenced by or reacting against Pynchon and company.

TWD: Thank you very much for your time. I really enjoyed speaking with you and learning more about you and your work.

David: It’s been a pleasure.

David's Favorite Authors

Thomas Pynchon

Don DeLillo

James Joyce

E. M. Forster

Richard Powers

And Some Favorite Books

V.

Gravity’s Rainbow

White Noise

Mao II

Grendel

Operation Wandering Soul

David Cowart took his bachelor's degree at the University of Alabama. After teaching in Ethiopia in the Peace Corps, he took an M.A. at Indiana University, then served two years in the U.S. Army (in Panama). He took his doctorate at Rutgers University in 1977. Professor Cowart has since taught at the University of South Carolina, where he has been named a Louise Fry Scudder Professor and a Board of Trustees Professor. For three years, in the mid-nineties, he served as Director of Graduate Studies in English. He has been honored with a number of teaching awards, as well as important grants and fellowships, including an NEH Summer Stipend and a year-long NEH Fellowship. He has held Fulbright chairs at the University of Helsinki and at Syddansk Universitet in Odense, Denmark. In addition to lecturing in Latvia, Germany, and the Czech Republic, he has presented keynote addresses at international conferences in England, Poland, Japan, and Germany. In 2005, he toured Japan as a Fulbright Distinguished Lecturer. He is a consulting editor for the journal Critique.

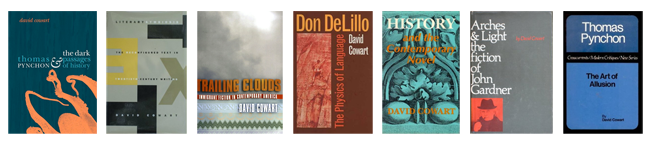

In his major scholarly work, Professor Cowart has focused on American fiction in the period after 1945. In addition to the books listed on his Amazon.com author page, he is the author of approximately one hundred articles, notes, and reviews. His book on Don DeLillo won the SAMLA Studies Award in 2003. He is now working on a seventh book, in which he examines the idea of literary generations in the postmodern period.

READ PART I OF THE INTERVIEW: David Cowart Interview

ISSUE:

S U M M E R

2012

SUPPORT THE ARTS

GET A T-SHIRT

DONATE TODAY!

By accessing this site, you accept these Terms and Conditions.

Copyright © 2010-2012 TheWritingDisorder.com ™ — All rights reserved